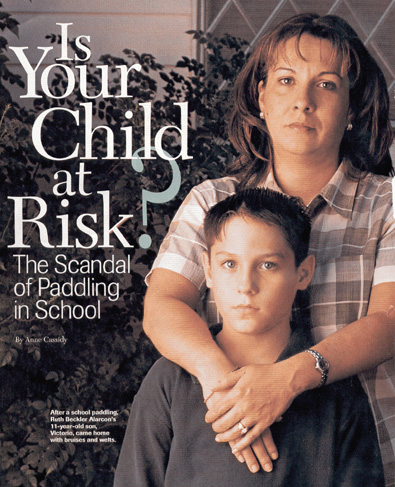

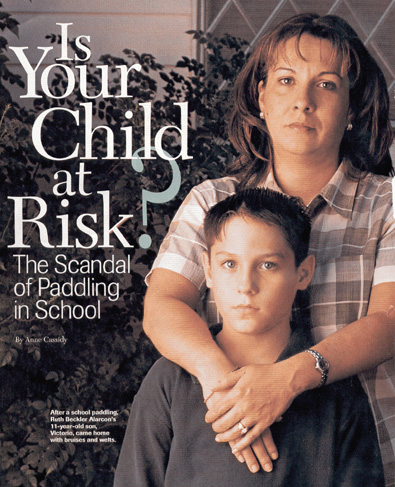

After a school paddling, Ruth Beckler Alarcon's 11-year-old son, Victorio, came home with bruises and welts.

Is Your Child at Risk? -- The Scandal of Paddling in School

By Anne Cassidy

Family Circle, November 1, 2002

Ruth Beckler Alarcon knew something was wrong when her 11-year-old son, Victorio Beckler, came home from school one day last September. After a little coaxing she soon learned that the principal had hit Victorio three times with a wooden paddle for failing to confess he had a small magnet hidden in his sock."The principal had me bend over and hold my pants legs," Victorio says. "It hurt." Ruth, who lives with her family in Pasadena, Texas knew that paddling was legal in her state, but this was too much. Victorio had bruises and welts on his buttocks, and the pain was so intense that he could barely reach down to tie his shoes for days afterward. Ruth wanted an apology from the school. But she never received one. Now she speaks out against corporal punishment "I want everyone to know that this can happen to their child," she says.

First-grader Jonathan Curtis of Demopolis, Alabama, knows all too well. Last year he was paddled on two occasions for picking his nose. The first time, his mother, Michaela, had agreed that Jonathan could be given three swats with a paddle after a teacher called to let her know that her son was misbehaving in the lunchroom. Michaela also said she wanted to be notified of any more paddlings beforehand. But the next day, when Jonathan picked his nose again, he was struck eight times-without parental permission. "It hurt so bad," Jonathan says in a small voice. "I was scared." Michaela knew nothing about the second incident until she saw her son's bruises that night. She took Jonathan to the emergency room and filed a police report. The next day she went to school for an explanation, but she didn't get a satisfactory one. And she still hasn't, even though she has contacted the governor and state legislators. "I want Jonathan to follow directions and behave," she says. "But how can I explain to him that he should trust teachers when a teacher left him black-and-blue? Kids need discipline, not abuse."

Is Corporal Punishment Legal?

Shocking as it may seem, the answer in many states is yes. Depending on where you live, it is legal for a teacher or principal to hit a child with a wooden paddle. Although corporal punishment is banned in almost every industrialized country in the world, here in the United States almost half of all states (23) still allow it. And while the number of school paddlings has dropped, an average of 2,000 students a day still receive corporal punishment for such offenses as skipping school, disrupting class, talking out of turn, or sometimes much more trivial ones, as Jonathan, Victorio and countless other children and parents have learned.The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association, the PTA and many other national organizations have called for an end to this practice. Yet a landmark 1977 Supreme Court case did not find paddling to be cruel and unusual punishment. Without a national law to ban it, the decision of whether to allow this form of discipline is up to individual states.

Paddling flourishes in what some call the "belt belt"-- rural, Southern states such as Mississippi, where one out of every ten school children is struck, and Texas, which accounts for nearly one-fifth of all paddlings in the country. Nine percent of students in Arkansas and six percent in Alabama are paddled each year. Other paddle-prone states are Tennessee, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Georgia and Missouri. Corporal punishment is allowed elsewhere in the country, too, including a few school districts in Ohio, Pennsylvania and other states. Paddling survives because enough educators, legislators and parents in these states believe it works, often citing the saying, "Spare the rod, spoil the child" or pointing to the fact that they were spanked as kids and turned out fine as evidence.

Dangerous Discipline

But critics take a sharply different view, calling corporal punishment harmful to children. They believe there are better ways to make kids behave. "When you hit a child, you are putting at risk his physical and psychological health and teaching him that violence is O.K," says Nadine Block, executive director of the Center for Effective Discipline in Columbus, Ohio, a national organization promoting nonviolent discipline. "You're not teaching him what you want him to learn because when a child is angry and fearful no constructive teaching goes on."While some children paddled at school suffer no lasting ill effects, others take it hard. Physically, a small percentage of children suffer severe bruising and internal injuries, and two students have died from their beatings, according to Irwin Hyman, Ed.D., professor of school psychology at Temple University and director of the National Center for the Study of Corporal Punishment and Alternatives. "The bruises caused by paddling would result in child abuse charges if inflicted by anyone other than an educator," notes Dr. Hyman, co-author of Dangerous Schools (Jossey-Bass). This is because in many states teachers who paddle are protected by law against child abuse charges.

The psychological effects can be just as devastating. Victorio Beckler's grades plummeted from As to Ds after he was paddled. His mother moved him to another school soon after the incident. And Jonathan Curtis lived in fear for weeks after his paddling, constantly asking his mom, "How many times will they hit me? How hard will they hit me?"

"He was actually scared the teacher would come spank him at home," says Michaela. In fact, one to two percent of paddled children are made so distraught by the experience that they develop post-traumatic stress disorder, Dr. Hyman says. Older children may become aggressive, act out, fall behind in school and lose interest in activities. Younger kids are likely to regress to babyish behaviors and develop stomachaches or other physical symptoms of stress. Understandably, many paddled children don't want to go back to school. For many, one of the most troubling aspects of corporal punishment is its inequity. Far more boys than girls are paddled, and while African-American children represent 17 percent of the nation's public school students, they receive 37 percent of the paddlings, according to the Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights.

The Pros and Cons of Paddling

Given all the strikes against it, why does corporal punishment still occur? Those who support it say that physical force, or the threat of it, keeps kids in line. "What we're interested in is being able to say, 'If you don't behave, you're going to be paddled,'" says Linda Belcher, former principal of Mount Washington Elementary School in Kentucky, who believes corporal punishment should be used only when appropriate and as a last resort. Last year Belcher sought unsuccessfully to reinstate paddling at her school, where it had been banned years earlier. "People say that paddling is harmful, but my concern is the lack of control I'm seeing in children."Pain can be a great motivating force, believes Robert Surgenor, a former detective in Berea, Ohio, and author of No Fear (Providence House), a book on corporal punishment. "Our culture has given us permission under certain circumstances to inflict pain on a person if he fails to comply with authority," says Surgenor. He notes that there has been no paddling in his local schools for over 20 years, but assaults against teachers have increased by 450 percent since 1980. "We're spanking our children less and our kids are becoming more violent," he says. When paddlings do occur, most administrators follow protocol, seeking permission from parents, having a witness on hand, and meeting other requirements. Indeed, teachers and administrators who paddle believe in what they do and are usually backed by parents in their district. Gary Bolton, administrative assistant at Cherokee Elementary School in Memphis, Tennessee, is a well-loved figure at his school. Yet he is also his school's chief dispenser of corporal punishment, ruling the lunchroom with his wooden paddle. "The kids want discipline," he says. "And most of their parents are behind it."

While pro-paddling educators say the practice is needed to maintain discipline and is used only as a last resort, critics disagree. For one thing, they say, corporal punishment doesn't work. For another, the punishment seldom fits the crime. "We identified schools that paddle and schools that don't and found no difference in discipline. The schools that didn't use corporal punishment didn't get worse," says Dr. Hyman. "We've also looked at the argument that corporal punishment is used as a last resort and found that there was no relationship between the nature of the offense and the force of the beating."

Rhea Cherrith of Steele, Missouri, would agree with that. Her five-year-old son, Josh, was paddled for whistling in school. Rhea had recently moved to Missouri from out of state and had not yet signed the paperwork that would have exempted Josh from corporal punishment. The experience sent Josh into a tailspin. "When he came home he was in a rage. He just about turned the house inside out," Rhea says. She knew she had to do something. "I'm Josh's mother and his protector," Rhea says. So she too has joined the fight to ban corporal punishment.

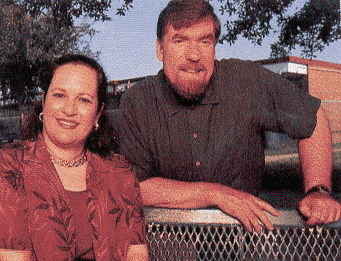

Fighting for paddle-free schools: Laurie Bricker, president of the Houston school board and Jerome Frieberg, Ed. D., of the University of Houston. Parents, psychologists and others are chipping away at the practice one district at a time in hopes that someday the whole country will be paddle free. Nadine Block spent nine years trying to affect change in Ohio. Ironically, even though lawmakers argued that paddling wasn't harmful, Block was often escorted out of their offices for carrying a paddle because it was considered a weapon. Jimmy Dunne, a former math teacher in Houston who once witnessed a brutal paddling that left an 11-year-old boy begging for mercy, founded a group called POPS (People Opposed to Paddling Students). Dunne takes heart from a recent ban on corporal punishment in Houston schools. "Now 200,000 more kids are going to paddle-free schools," he says. Laurie Bricker, president of the Houston school board, cheers the change in her city. Also a former teacher, Bricker vowed never to witness corporal punishment again and has been fighting for a ban for years. In Houston, at least, the struggle has paid off.

Success Without Spanking

What happens in paddle-free schools? All kinds of good things. Take Marshall Middle School, located in one of the oldest barrios of Houston. A few years ago Marshall used corporal punishment, which was still allowed in Houston at the time, and had problems typical of inner-city schools. "The kids were difficult to manage. They were bringing problems in from the outside," says principal Juan Gonzales. Marshall stopped corporal punishment before it was legally banned because administrators didn't think it worked. "We chose to empower students instead of making them comply," Gonzales says. Marshall began using a discipline program called consistency management and cooperative discipline. Designed by Jerome Freiberg, Ed.D., of the University of Houston, the program has improved some of the most challenging inner-city schools in Newark, Chicago, Los Angeles and Houston. It tries to engage as many kids as possible in the life of the classroom. One day when a substitute teacher didn't show at Marshall, one of the students, a former gang member, passed out papers, led a discussion, then had classmates write an essay. When this tough guy turned in the folder of completed work at the end of first period, the principal was stunned. The class was so well behaved, he had no clue the sub didn't show. "Amazing things happen when there's respect and kids take responsibility," Dr. Freiberg says.Getting rid of corporal punishment in school means fixing little problems before they become big. It means using peer mediation, in which students counsel students, and positive behavioral controls, such as incentives for good behavior. Often there's a psychological component. Students learn to respect themselves and others, and to identify their feelings instead of using fists or angry words. "Once you've tried alternative forms of discipline, you realize you can manage difficult children without violence," says Terry Kopansky, Ed.D., principal of Harris Hillman School in Nashville. "You have to figure out what motivates them."In his years as an educator Dr. Kopansky has learned to make the punishment fit the crime. If a child marks a table, he has the child clean the table and several others too.

"Even if our district went back to corporal punishment, I would never use it," says Ruth Ann Spatar, principal of Green Elementary in Logan, Ohio. "Kids might fear getting a swat, but I see the same fear when I tell them to call their mother and tell what they've done." Keeping the personal touch, believing that students will behave, and providing fair punishments when they don't makes paddling seem irrelevant. "We put a lot of our emphasis on counseling," says Gonzales. "We're like a family."

What Parents Can Do

Moms and dads are the true foot soldiers in the battle against corporal punishment, exposing harsh punishments and keeping the pressure on paddle-prone educators, school board members and state legislators. Here's how you can help put an end to the practice -- and stay on top of your own school's discipline policy, as well.1. Find out whether your state allows corporal punishment in school by visiting the Web site of the Center for Effective Discipline. (See "For More Information")

2. Ask for and study a copy of your school's discipline policy. Whether or not your school paddles, you and your child should understand school rules and penalties for violating them.

3. If you live in a state that allows paddling, familiarize yourself with the opt-out policy. Parents often fail to read the fine print of the rights and responsibility cards they sign at the beginning of the school year. Do you need to sign a form, write a letter or make a phone call to ensure your child won't be paddled? If so, do it. Let your school know you understand kids misbehave-you just don't think they should be paddled for it

4. If your child is paddled at school, photograph any injuries. Take your child to a doctor or the emergency room. Find out if there were any witnesses to the paddling. Report the injury to the child protective agency in your town. Realize, however, that teachers and principals are often protected by laws in pro-paddling states, making it difficult for parents to prevail in court.

5. Join organizations. Most states that allow school paddling also have grassroots groups that fight against it. 6. Can't find an organization in your area? Then start one. The Center for Effective Discipline suggests these grassroots strategies:

- Meet with local school boards and request a ban on paddling.

- Survey local school districts and collect their discipline policies.

- Prepare fact sheets on the status of corporal punishment in schools.

- Learn about and keep track of injured children in your school district or state.

- Identify schools that are close to banning corporal punishment and offer to help.

- Contact state legislators. Write a petition and start letter-writing drives to lawmakers.

- Seek media attention by encouraging parents of paddled children to speak out. Share information you have collected with reporters.

For moms like Michaela Curtis, the more parents involved, the better. She knows it will be an uphill battle to ban corporal punishment, but she's not giving up. Michaela believes there are better ways. She recalls a time when her eldest son was ordered to plant flowers as punishment for misbehaving in school. It taught him responsibility and the value of hard work. "After a few months the flowers were still blooming and he was proud of them," she says. 'The punishment served a purpose." It's the kind of change she hopes will take root everywhere.

For More Information

To learn more about corporal punishment in schools, state laws, and what you can do to put an end to school paddling nationwide, log on to these organizations' Web sites:

- Center for Effective Discipline: www.stophitting.com

- Project NoSpank: www.nospank.net

- Tennesseans for Nonviolent School Discipline: www.geocities.com/forkidsake

- The No-Spanking Page: www.neverhitachild.org

- National Center for the Study of Corporal Punishment and Alternatives: www.temple.edu/education/pse/NCSCPA

FC

|

HAVE YOU BEEN TO THE NEWSROOM? CLICK HERE! |