MASON The deputy's headlights broke the middle-of-nowhere October darkness as he rolled down the red-dirt road to a campsite.He fixed his cruiser's spotlight on the scene: tent silhouettes, a small fire and as Mason County Deputy Harold Low would later describe in his official report 17-year-old Chase Moody chest-down, pinned to the ground by three camp counselors.

Low handcuffed one arm and flipped the boy over. That's when he saw the vomit and realized that Chase wasn't breathing.

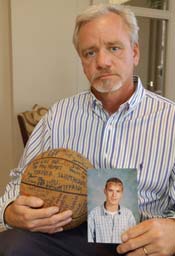

Photo: Tim Sharp, Associated PressDallas attorney Charles Moody holds a basketball and a portrait of his son Chase Moody. Chase died at a wilderness camp last October after being restrained.

The Richardson teenager did not make it off the hilltop alive that night, and he wasn't the first to lose his life this way.

Moody was one of thousands of Texas children and tens of thousands nationwide who have become part of a booming $60 billion industry that promises to reform teens who have veered off the path of acceptable behavior.

Whether they have serious psychological problems, rebellious streaks or parents who have lost their patience, these children soon find themselves at the mercy of a system for which there is scant oversight or accountability and spotty record-keeping.

And there is no easy way for parents to compare the track records of various programs.

The inability to rein in the widespread use of improper physical restraints, such as the one the state investigators believe was used on Chase Moody, is emblematic of efforts to regulate the industry itself.

That night, at the On Track therapeutic wilderness program, Chase Moody became one more name on a list of what are believed to be hundreds of youth and adults in this country who have died in the past decade after being held in a physical restraint in a residential care setting.

Chase Moody also became at least the 44th youth or adult in Texas to die under similar circumstances since 1988. And in the aftermath of his death, Chase has become the latest reminder of state lawmakers' unwillingness to pass tougher laws governing restraint that could prevent other people from dying this way or even to better track the body count.

"How many more kids have to die before they do something about it?" Chase's father, Dallas lawyer Charles Moody, asked.

In 1998, at the request of the Hartford (Conn.) Courant, the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis estimated that 50 to 150 adults and children die each year during or shortly after being placed in a restraint. The analysis was based largely on data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and New York, the only state that in 1998 investigated all deaths in institutions.

The Courant confirmed 142 restraint-related deaths of adults and children since 1988. The true death count, according to the Courant, could be three to 10 times higher because many cases are not reported to authorities, according to the statistical estimate.

In 1999, a report from the U.S. General Accounting Office pointed out the government's deficiency. (Read more about the GAO's findings about the lack of regulation and adequate record-keeping of the use of restraints at statesman.com/specialreports/restraint/).

Four years later, no one knows the toll, largely because efforts to track or research such deaths have not taken hold in every state or at the federal level.

At least two more youths have died this year after being restrained: one in Colorado, the other in California. Chase Moody was at least the third youth to die in Texas last year.

Just two days before Chase's death, on Oct. 12, Maria Mendoza stopped breathing moments after being placed in a restraint by staff members at Krause Children's Center in Katy, according to a Department of Protective and Regulatory Services investigation. The Harris County medical examiner's office ruled that the 14-year-old died of "mechanical" or traumatic asphyxiation. In simple terms, that means external pressure or the position of her body prevented her from breathing.

In February 2002, 15-year-old Latasha Bush died several days after being restrained by staff at the Daystar Residential Center in Southeast Texas, a DPRS investigation concluded. Again, the medical examiner listed mechanical asphyxiation as the cause of death.

Travis County Deputy Medical Examiner Elizabeth Peacock ruled that Chase Moody died the same way, choking on a last supper of macaroni and green beans as crushing pressure on his torso forestalled any draws for air.

The Brown Schools, which owned the camp and based its administrative operations in Austin, have disputed the autopsy with their own expert, who contends that Chase died from excited delirium, which means he became so agitated and enraged that his heart stopped. (Read more about the medical argument of traumatic asphyxia vs. excited delirium at statesman.com/specialreports/restraint/.)

Regardless, critics say the tragedy could and should have been prevented. As Charles Moody told the state Senate Health and Human Services Committee in April, Chase "choked on his own vomit, and nobody even knew it."

Little enforcement

Prone restraints, such as the one Chase Moody wound up in, are discouraged in Texas and many other states, and entirely banned in at least three.

Texas prison officials consider such restraints so dangerous that they ban guards from employing the techniques on even the most violent inmates.

Prison rules prohibit pressure from being applied to a convict's neck, back, chest or stomach and mandate that "the supervisor shall ensure the offender is continuously monitored to identify breathing difficulties, loss of consciousness or other medical concerns, and seek immediate medical treatment if necessary." They also mandate that offenders shall be placed onto their side or into a sitting position "as soon as practicable."

"Once they go to the ground, there can be problems," said Larry Todd, spokesman for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

Texas also is one of a handful of states with strong regulations limiting the use of restraints in therapeutic settings. However, regulators lack effective means to enforce their own rules. And in Texas, even watered-down legislation to ban the potentially fatal restraints has little chance making a difference, even if approved.

The Texas Department of Protective and Regulatory Services, the agency responsible for regulating the use of restraint in private 24-hour residential settings for youth, licenses nine therapeutic wilderness programs and 77 youth residential treatment centers statewide. The agency's residential child-care licensing division, which receives a budget of $2.2 million annually, also is responsible for 65 emergency shelters and the state's thousands of foster and adoptive homes.

The division's 27 inspectors and 12 investigators visit 24-hour care facilities, which include wilderness programs and residential treatment centers, every 5 to 12 months and every time a report is received related to child abuse, neglect or other violations.

The only available records from the DPRS, which run from 1998 to the present, show that at least six youths have died during or shortly after being placed in a physical restraint, including an additional death at a facility owned by the Brown Schools.

Much of the agency's investigations are kept confidential, and the documentation released to the American-Statesman is far from complete; often missing are dates of death, ages, circumstances and any supporting documentation for the findings.

In one instance, a letter summarizing a 2000 restraint-related death at a Brown Schools center in San Antonio was a terse four paragraphs that gave few details.

More details

The only details released from that file were in an attached press release from the Brown Schools.

In it, the Brown Schools called "natural" the death of a 9-year-old boy who, according to court documents, was held to the ground until he vomited and stopped breathing.

Independently, the Statesman has verified through media reports, court documents and watchdog groups at least 10 more juvenile deaths that occurred between 1988 and 1998 in other Texas facilities, some of which were licensed and regulated by the DPRS, including three more restraint-related deaths at facilities owned by the Brown Schools.

More deaths have been reported by various advocacy and watchdog groups, but the details of those could not be independently verified.

Previously, some restraint-related deaths were simply ruled natural and the details never passed on to any agencies. That happened in the case of 16-year-old Dawn Renay Perry, who died in 1993 after being placed in a restraint at the Behavior Training Research center in Manvel near Houston. Last summer, after a review, the Harris County medical examiner switched the cause of death from natural to accidental. The girl's mother has since sued the facility's owners.

Current legislation aims to clean up the reporting process, as well as to standardize the rules on restraint for every facility that uses the technique.

The bill would outlaw restraints that obstruct a person's airway, impair breathing or interfere with someone's ability to communicate.

It would restrict, but not prohibit, the use of prone restraints or restraints that place a person on his or her back. It also would establish a multi-agency committee to write new regulations governing the use of restraints and to develop a better system to collect and analyze data related to it.

But the bill, sponsored by state Sen. Judith Zaffirini, D-Laredo, stops short of ascribing criminal penalties, something advocates have long asked for and an oversight parents of the dead are demanding.

"This bill does nothing," said Charles Moody, who would like to see violators face felony charges. "It's a joke. All it does is create a focus group to talk about this issue."

Or as Jerry Boswell, president of Texas chapter of the Citizens Commission on Human Rights, a mental health watchdog group, said, "It deceives the public into thinking something meaningful has been done, and it hasn't."

Aaryce Hayes of Advocacy Inc., a federally funded nonprofit group with the mandate to review potential cases of abuse and neglect involving people with disabilities, said the bill would at least lay the foundation for future legislation.

"It's a start," Hayes said. "If it did (have criminal penalties), we wouldn't be able to get the bill passed, just like the last two sessions."

Similar restraint bills have died in the House twice before amid opposition from some medical and psychiatric groups, as well as from corporate lobbyists, whose ranks once included Gov. Rick Perry's chief of staff, Mike Toomey, a former lobbyist for the Brown Schools who worked his way through college in a Waco residential treatment center for troubled youth.

Zaffirini said she would have preferred criminal penalties but that because such penalties could send more people to prison, the potential fiscal impact in budget-cutting season would kill the bill.

"It's been controversial in the past, and I don't quite understand why," Zaffirini said. "It's confounding."

The Democrat House members' protest over redistricting last week only lessens the chances of the bill's passage.

A last-resort tool

In the world of therapy, from wilderness camps to private treatment centers, restraint is supposed to be a last-resort emergency tool for residents who pose a danger to themselves or others.

Instead, Hayes said, "What we find quite often is, it wasn't an emergency until staff intervened."

State reports show that in these facilities, the use of restraint is widespread. Records also show that restraints are used as a form of punishment, for the convenience of staff or to simply take control of a situation.

For example, at a youth ranch outside Brownwood, state documents show, children were being restrained for crying or simply for moving their hands. At least one resident was restrained for refusing to go to school. In another instance, a 16-year-old boy was belittled, threatened with the suspension of home visits and grabbed in the face before staff members took him to the ground, where he died in 1999, according to a DPRS report.

The report says there is strong evidence that the boy "stopped struggling with staff and was largely unresponsive long before the restraint was terminated."

The report also says it wasn't the first time restraints were misused at the New Horizons Ranch.

"Serious incident reports indicate that the staff sometimes used restraint as punishment, for their convenience or when the child was not necessarily a danger to themselves or others," the state report says.

Such reasons all violate DPRS regulations but not the law. And the punishment for breaking the rules is tantamount to forcing the violators to promise that they'll try not to do it again.

The state's December 1999 response to each of the findings at New Horizons: Correct the violations immediately.

"After that November investigation, we went out four times during the course of calendar year 2000," said Geoffrey Wool, the agency's director of public relations. But the facility was not placed on any kind of probation.

New Horizons has not received any serious citations since at least January 2002.

When deaths occur, in Texas or elsewhere, rarely are they prosecuted. For families of the lost, civil lawsuits often are the only recourse. But most of those get settled for confidential sums outside the courtroom and beyond public scrutiny.

In the past five years, the time span for which records are available, no restraint-related death has led to the revocation of a facility's license in Texas. And the DPRS has levied no fines against offenders.

"What we are trying to do is work with all these providers to make sure they provide the care these kids need," Wool said. "We're not out to hammer providers. We want to help them so they're there to help our kids."

When a facility is cited for any violation, the operators draw up a "corrective action plan." And, typically, that's it.

There's no "simple way," Wool said, to determine how many improper restraints that did not result in death were investigated or whether they led to serious injuries.

However, inspection and complaint investigations since January 2002 have recently been put on the agency's Web site and can be searched at www.tdprs.state.tx.us.

An American-Statesman review of those records shows that statewide over the last 17 months, the DPRS has handed out at least 150 restraint-related citations for violations ranging from minor paperwork infractions to causing serious injury.

A 'seminal event'

Before Chase's death, On Track had never been cited for using improper restraints, although its training methods have been called into question in prior complaints filed with the state that were later verified.

Yet after the onslaught of media attention surrounding Chase's death, state licensing investigators issued a scathing report that cited On Track for 28 violations, ranging from improperly restraining Chase as punishment and using a prohibited method of restraint to improper record keeping and numerous procedural violations.

Officials with the Brown Schools have repeatedly said the incident was handled properly.

However, former Brown Schools CEO Marguerite Sallee recognized the gravity of the situation. She told a meeting of reporters and editors at the American-Statesman on the day the state's report was released that Chase's death could be the "seminal event that could bring the whole company down."

Not six months later, she has left the company to become staff director for the United States Senate subcommittee on Children and Families in Washington, a move she said was unrelated to the Chase Moody incident.

It's unclear what would've happened to the wilderness program had it remained open for business.

The company closed On Track in December after losing the lease to the 6,000-acre exotic-game ranch where the camp was located. Several months later, it sold off all its residential treatment centers in the country, including facilities in San Marcos, Austin and San Antonio. Company officials say the plans to sell the facilities were made before Chase's death.

A dispute over the state's findings is the company's only lingering business with the Texas agency.

That argument centers on whether the restraint used on Chase was performed the right way and for the right reasons.

In their report, state investigators contend that it was neither.

On Oct. 14, the day's activities had ended. According to Mason County Sheriff M.J. Metzger, Chase and other boys had been told to stop talking and go to sleep.

Mason County Chief Deputy Sheriff Bill Price said that according to his investigative notes, Chase wouldn't be quiet and was told to sleep outside as punishment.

Words were exchanged. Chase, according to a police report, aimed racial slurs at the Hispanic counselors. Brown Schools officials, without giving specifics, say Chase then became violent and lashed out at the staff, placing both himself and the others at risk.

The sheriff's investigation tells a more detailed story. According to Price, who based his comments on official statements from all those involved in the incident, Chase was arguing with one staff member, and the other two were standing a few steps away.

According to the statements, Price said, Chase walked toward the lone counselor and "kind of shoved him out of the way." The actual nature of the physical contact, Price said, was described by different witnesses as a bump, shove or push.

"We've got different stories," Price said. "I think everybody agreed there was physical contact."

The counselor Chase confronted, along with another staff member, then placed Chase in a physical restraint referred to in the industry as the team control position, wherein staff members interlock legs with the subject, pull back the wrists and cup their hands on the person's shoulder.

From there, all parties agree, they fell forward. Price said the third staff member then joined in the restraint.

"On all these statements here, the staff keeps asking him to comply and they would let him up, but he kept resisting," Price said, describing the details in the affidavits.

"We have one resident saying he heard Chase saying he couldn't breathe; we've got two of them saying that."

After he was contacted by radio, it took Deputy Low about 13 minutes to wind his way back through the ranch to the campsite.

In the incident report, Low wrote that when he aimed his spotlight at the scene, he "saw three counselors sitting on the subject, lying face down," Price said.

The Brown Schools has repeatedly denied that any pressure was placed on Chase's back.

The state's findings in the separate licensing investigation question whether the situation qualified as an emergency and accused the staff members of taunting Chase with remarks that included, "Boy. Who you calling boy?"

In addition, the report says: Chase was "subjected to cruel and unnecessary punishment when he was restrained for talking."

The restraint was "inappropriately implemented, as it employed a technique that is prohibited by obstructing the airways of the child, impairing his breathing."

The staff "did not follow the facility's policies and procedures in handling the misbehavior of a resident, which resulted in a restraint and death of the child."

The staff "did not document the total length of time the child was restrained."

"The bottom line: Chase Moody did not pose an emergency to himself or anybody else when he was put in this restraint," said David McLaughlin, a lawyer working with the Cochran Firm, who is assisting high-profile lawyer Johnnie Cochran on the potential civil suit. "These three people in the take-down . . . I'm not going to call them victims, but they were put in circumstances without the proper tools or skills to handle the situation."

Sallee called the findings disappointing, one-sided and inaccurate.

"All they were doing was trying to protect themselves and the others," Sallee said of the staff members who placed Chase in the restraint. "The child was violent that night and had a history of violence."

Howard Falkenberg, a spokesman for the company, responded Thursday with this prepared statement:

"The death of a student last year in the On Track program is a tragedy that profoundly saddens us, and our sympathies remain with his family. At the same time, we know that our staff acted appropriately in very difficult circumstances. These are caring men who were devoted to helping the young people in their charge, and they were properly trained to do their job."

An attorney's quest

The Brown Schools have been involved in four other restraint-related deaths over the past 15 years. And the company has received dozens of improper restraint and licensing violations at its various residential treatment centers, according to an American-Statesman review of licensing records. The last youth to die before Moody after being restrained in a Brown Schools program was 9-year-old Randy Steele, whose death was written up in the four-paragraph memo from the DPRS.

Like many children with attention-deficit disorder, Randy was bored with school, too smart for his own good and constantly in trouble. When he was diagnosed as bipolar, his father enrolled him in short-term therapy in Las Vegas.

But Randy needed more, and Nevada doesn't offer long-term care.

The youngster was sent to the Brown Schools' San Antonio treatment center, Laurel Ridge, which was supposed to correct his hyperactivity and behavioral problems. According to court documents filed by a lawyer for the boy's mother, Randy was restrained at least 25 times in less than 28 days.

He died after the last one in February 2000, after orderlies physically restrained the boy, who had launched into a toy-tossing temper tantrum after refusing to take a bath. According to court records, the orderlies held Randy chest-down until he began to wheeze and vomit. They then turned him on his side and realized that Randy had lost his pulse.

No criminal charges were filed in the case. The DPRS did not cite Laurel Ridge for any violations. And Randy's mother never learned the details of what really happened that night.

Like other families who have lost children this way, Randy's mother, Holly, turned to the civil courts. The case was headed for a jury in October.

"The day we were supposed to start trial, the Moody incident happened," Holly Steele said. A few months later, she settled the suit with Brown outside of court for an undisclosed amount.

On the night Chase died, Charles Moody fell asleep on the couch toward the end of the Monday night football game.

The phone rang shortly after midnight.

Photo: Larry Kolvoord, American-StatesmanChase Moody's stepmother Tina Moody hugs Salvador Sanchez after a state senate hearing on proposed legislation that would regulate restraint methods. Sanchez's 14-year-old niece, Maria Mendoza, died just two days before Chase's death after being placed in a restraint by staff members at Krause Children's Center in Katy.

Since, Charles Moody has been searching for justice somewhere, somehow.

He's held meetings with prosecutors and legislators. He's even gone as far as hiring Cochran, the same lawyer who successfully defended O.J. Simpson, to potentially take civil action against the Brown Schools. And he's shared tearful embraces with other parents, such as Holly Steele, who have been through all this already.

What Moody knows all too well, though, is that this crusade will not bring Chase back.

"The main thing I want," Moody said at his Dallas law firm shortly after his son's death, "I can't have."

josborne@statesman.com; 445-3621

mward@statesman.com; 445-1712