Plaintiff prevails in lawsuit alleging that school district failed to stop abuse for decades.

The most any school official did was threaten disciplinary action.

MICHIGAN - Sarah K., 31, sits in a restaurant, her infant son, Max, next to her playing quietly in a baby seat and staring at passersby. She can’t help but smile whenever their eyes meet.

The boy helps her to smile a lot these days, but he also reminds her of her responsibility to nurture and protect Max, her fourth child.

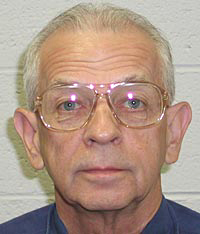

John Lomnicki is serving 18-36 years in prison for criminal sexual conduct.

Her sense of obligation is heightened because when Sarah was young, she was the victim of a career child molester — a teacher whose bosses chose to transfer him from school to school rather than report repeated student complaints to police, or remove him from the classroom.

Sarah shudders to think of any child suffering abuse because school officials didn’t react forcefully.

“If a kid in my neighborhood said, ‘Jimmy touched me,’ you better know goddamn well I’m gonna call the police,” Sarah says. “On a moral level, you have to answer to yourself.”

Her comments are prompted by a discussion about John Lomnicki, 69, a convicted pedophile who is serving 18 to 36 years in prison for sexually molesting Sarah from 1982 to 1984, from the time she was 9 until she was 12.

Allegations contained in a lawsuit filed against Lomnicki and the Roseville Community School District (RCSD) assert that Sarah was far from his only victim.

Between 1975 and 1993, the lawsuit alleges, the RCSD was made aware of at least 14 incidents of alleged molestation involving Lomnicki, an elementary school teacher.

Sarah K. at home

Sarah is outraged that a man suspected of abusing so many children for so many years was allowed to remain in the classroom for so long.

The lawsuit alleges that school district administrators never reported abuse complaints to police. District officials themselves testified that Lomnicki was only removed from the classroom after police began a criminal investigation based on complaints that police received independently, not from district officials.

Prior to that, testimony from the administrators themselves shows, the most any school official did was threaten disciplinary action via two written, sealed reprimands placed in Lomnicki’s personnel file.

Whenever too many allegations arose at one school, RCSD administrators would transfer him to another district school without informing administrators at the new school of the complaints against him, the lawsuit alleges.

In each new school setting, he was given the same responsibilities, and toward the end of his career, he was granted a federally funded tutoring position that gave him one-on-one access to children and a private room.

After police informed RCSD officials that it was conducting a criminal investigation of Lomnicki in early 1993, testimony shows, it took them an additional two months to remove him from his tutoring post and cut him off from children.

“This was the same time period when Lomnicki was molesting Jane Doe,” the lawsuit alleges.

Jane Doe

Elizabeth Slinde, now a Macomb County commissioner, knew about complaints against Lomnicki

Jane Doe entered Lomnicki’s orbit in 1992, when she was a kindergartener and he was her one-on-one reading instructor at Eastland Elementary School in Roseville.

Jane, now 16, testified in a deposition that Lomnicki sexually molested her at least five times, rubbing her, grabbing her and penetrating her vagina with his fingers. Jane testified that Lomnicki took her into the boys’ bathroom, where he hung her by her jacket hood on a hook on the door.

Jane testified that Lomnicki used tools, a hockey mask, which he wore on two occasions, and a rope, which he once used to tie her wrists while she hung from the hook. She says he hit her with a miniature wooden bat, and slapped her face. She said he threatened to kill her if she told anyone what he was doing.

Lomnicki, imprisoned at Ryan Correctional Facility, declined to be interviewed for this story. All current and former RCSD officials contacted by Metro Times refused to answer questions about Lomnicki.

Jane’s mother sued RCSD in 1996, one year after Lomnicki was convicted in criminal court of first- and second-degree criminal sexual conduct against Sarah K. Jane’s mother is identified in the lawsuit as Sally Doe.

The civil suit — which said the RCSD’s “deliberate indifference” allowed Lomnicki to abuse Jane and violate her civil rights — was settled in U.S. District Court in Detroit last month. The amount of the settlement was not disclosed, and all parties are prohibited from disclosing it. However, a federal mediation panel that reviewed the case ruled that it would warrant a $7 million award, Jane Doe’s attorney says.

John Kment, current superintendent of Roseville Community Schools

The award will be paid by the School Employers Trust, School Employers Group (SET SEG), an insurance pool organized by the Michigan School Boards Association.

According to Tim Mullins of Cox, Hodgman & Giamarco, the law firm that represented RCSD in the civil trial, SET SEG made the decision to settle.

Ron Greve, the RCSD’s general counsel, says: “It was the insurance company’s call. Under the language of the contract, they have the exclusive right to settle claims they are defending.”

Neither Mullins or Greve would discuss the defense’s position in detail — or explain why the case was prolonged for eight years — but Mullins says that Lomnicki has always denied molesting anyone.

When the civil case finally went to trial in federal court in January, it lasted exactly one day. SET SEG made an acceptable settlement offer the day after the jury heard opening arguments.

“Disagreement over the amount of settlement didn’t help,” Greve says. “The parties were miles apart. They came together when it went before a jury. You’re at the point where you’re either going to settle it, or somebody is going to make the decision for you.”

Greve says the school district was always in favor of a settlement.

“Our position all along was that the case should have been settled,” he says. “The parties had been discussing settlement all along.”

Sally Doe’s attorney, Julie Hurwitz, executive director of the Maurice and Jane Sugar Law Center for Economic and Social Justice, disagrees with this view.

“I was told up to the very end there was no way they were going to pay,” says Hurwitz, who along with Thomas Stephens took leave from Sugar Law to pursue the lawsuit. “It was made clear to us from day one that they considered this to be a frivolous case.”

Hurwitz believes the district was more concerned about negative publicity than protecting children — a suspicion bolstered by testimony from a former RCSD superintendent.

“RCS would get reports and do their version of an investigation,” Hurwitz says. “This means it would be the teacher’s [Lomnicki’s] word against the student’s. RCS would go with the teacher and determine there was no merit to the students’ claims. It was a CYA [cover your ass] action rather than a move to protect children.”

Method man

RCSD administrators’ see-no-evil approach is reflected by the fact that police finally got wind of Lomnicki in 1993 through Sarah K., who was not a district student when he molested her.

Sarah, Lomnicki’s lone known off-campus victim, describes him as a calculating predator.

“He wedged his way into this life disguised as this normal, churchgoing, children-loving teacher, to get close to children,” Sarah tells Metro Times. “He needed punishment because he carried it out for so long.”

Lomnicki was Sarah’s in-home math tutor and next-door neighbor. He became her tutor after her parents divorced and her mother moved them to a home in Warren. Sarah was 9 years old and in the third grade.

“I’m terrible in math,” says Sarah, who is now married and a stay-at-home mother. “He offered his services so gallantly. He offered gifts. He was one of those creepy guys who would shake your hand and touch your shoulder.”

Lomnicki lived next door to Sarah with his mother. Upon learning of Sarah’s trouble in math, she says, Lomnicki approached her mother and offered his services, free of charge.

A Warren police report states that tutoring sessions were always held in Sarah’s bedroom. She tells Metro Times that the first few involved only tutoring. But she says poor performances on the tests he gave her would prompt lewd demands — he’d ask for a kiss on the cheek under threat of telling her mother of her poor mathematics skills.

The kissing progressed. To the lips. He put his hand inside her shirt. Then he had her remove her clothing and began performing oral sex on her.

“He’d do something until it felt normal,” she recalls. “And then he would do a little bit more.”

The time he spent tutoring became sporadic, she says. “He would often say things like, ‘Instead of that, why don’t you come sit on my lap and give me a kiss?’”

Handwritten notes kept by Lomnicki documented 15 sessions; he met with Sarah every six to seven days. He wrote that Sarah often pouted, was short-tempered and made little or no progress in math.

Asked where her mother was during these sessions, Sarah says she always left them alone. When the oral sex began, she says, she threatened to scream, and Lomnicki told her to go ahead. Her mother, he said, already knew.

Sarah says she would believe that until years later, when the criminal trial began. Then, she says, she realized that her mother never suspected a thing.

School days

Testimony gathered in the civil case alleges that Lomnicki’s usual hunting grounds were the RCSD schools where he taught. Within his first 20 years on the job, he worked at five schools in the district, which is bounded roughly by 10 Mile and 14 Mile roads, Little Mack and Groesbeck. Enrollment today is approximately 6,500 students, district officials say.

Administrators at three of the five schools where Lomnicki taught became aware of abuse complaints against him, testimony indicates.

Testimony by former Roseville school principal Elizabeth M. Slinde indicates that she heard student complaints but did not notify police, the Macomb County prosecutor or any other law enforcement agency. Slinde couldn’t even recall reporting the complaints to her superiors. She testified that she gave Lomnicki a verbal warning.

Slinde retired from RCSD in 1986. She has been a Macomb County commissioner representing Roseville and Eastpointe since 1979.

Sealed reprimands placed in Lomnicki’s personnel file indicate that other administrators who knew of complaints against Lomnicki were one-time RCSD Superintendent Frank C. Mayer and Leroy Herron, assistant superintendent under Mayer. Both Mayer and Herron have retired from the district. Neither could be reached for comment on the allegations in the lawsuit. Mayer, who now lives in Florida, did not respond to messages left at his home. Herron apparently still lives in the area.

Dorothea Sue Silavs, the district’s director of special education, filed a report with Child Protective Services in December 1994 suggesting that Jane Doe was being abused — by someone in her home. Though the report was filed after Lomnicki had been arrested for abusing Sarah K., Silavs wrote that the alleged perpetrator was “unknown.” Silavs admitted under oath that she knew the alleged offender was Lomnicki, that she had never interviewed Jane or Jane’s mother and that she had no basis for suggesting that Jane had been abused in her home.

Under the state Child Protection Act of 1975, school administrators and teachers are required to immediately report suspected abuse to at least one of three agencies — the county’s prosecuting attorney, the family independence agency or local police. This includes suspected abuse on or off school grounds, including a student’s home. Failure by any school administrator to obey the law is a criminal offense, punishable as a misdemeanor.

A statute of limitations exists on this law, according to William Harding, chief of operations for the Macomb County Prosecutor’s Office. Harding says anyone violating it must be prosecuted within six years of the date of the crime. He says the prosecutor’s office never examined whether administrators violated the Child Protection Act because the criminal investigation centered on crimes committed in Sarah K.’s home, and Sarah was not an RCSD student.

Touchy tenure

John Lomnicki’s teaching career began in 1960 at Fountain Elementary School. A minimum of seven allegations of inappropriate touching and child molestation surfaced during the 18 years he worked there, according to the civil complaint.

A Jan. 18, 1995, Warren police report says the first known incident took place sometime during the mid-’60s. In the report, Andy, the only male child included in Lomnicki’s list of alleged victims, told Warren investigators he was sexually assaulted up to 12 times while in Lomnicki’s third-grade class. The assaults occurred at various times of the day, sometimes after school, sometimes while Lomnicki’s students were seated and working, the report states.

Andy told police he was taken into the bathroom and forced to face the wall. Lomnicki would press his body against Andy’s, unzip his pants, and place the child’s hand on his penis.

Andy, who died in 2000, six years after an accident left him a quadriplegic, told nobody about Lomnicki’s molestations until he was an adult.

Retired Warren Detective Frank Spanke wrote in the 1995 police report that “after each incident, Lomnicki would warn [Andy] not to tell anybody, that [if] anything [was mentioned] to his parents about these incidents, that Lomnicki would in turn tell Andy’s parents that Andy was doing bad in school and failing subjects … behaving bad in class.”

The first apparent case of an RCSD administrator witnessing questionable behavior came during the 1971-72 school year. Beth, 40, testified during a deposition taken in January of this year that Lomnicki abused her repeatedly — four of five days each week — through the course of the entire academic year.

According to Beth, Lomnicki rubbed her back, put his hand into her pants and inserted his fingers into and kissed her vagina.

Beth testified that the principal of the school at the time once caught her and Lomnicki in a closet in his classroom during school. The principal opened the door just in time to find Beth pulling up her slacks, she testified.

She did not recall what transpired between the principal and Lomnicki, but she did recall being “very upset.” She was not, however, removed from Lomnicki’s class. There is no record that the principal, who is now deceased, did anything to discipline Lomnicki or report the alleged incident to his superiors or to police.

A chronological account compiled by Hurwitz’s team alleges that Lomnicki molested five more girls between 1975 and 1977. Alleged victims testified that he touched between their legs, rubbed their inner thighs, put his hands into their underwear and up their dresses. He would invite some to sit in his lap. He put his tongue in one little girl’s mouth on more than one occasion.

Elizabeth M. Slinde was principal at Fountain during these years. Documents prepared for the civil trial indicate she was made aware of three of the five cases. The first occurred during 1975-76.

Court papers filed by Hurwitz allege that a student named Gina told both her father and Slinde that Lomnicki had touched her inappropriately. The father, the account says, met with Slinde, who, according to Gina, said she did not see how it could have been possible. “Gina, with her father, demonstrated how Lomnicki touched her,” Hurwitz says. “Slinde said it was impossible, and sent her back to class.”

Slinde testified in the civil case that she did not report these incidents to police or even to the RCSD superintendent.

The district at that time had no established procedure for addressing suspected sexual abuse. According to Frank Mayer’s testimony during the civil proceedings, it was each principal’s responsibility to handle such cases. RCSD would not adopt a districtwide policy until 1992.

During a deposition in the civil proceedings, Slinde testified that, with no written procedure in place, she handled it by talking to Lomnicki and warning him not to touch children inappropriately.

But the verbal admonition apparently did not deter Lomnicki.

The following year, Lomnicki allegedly molested at least three more girls. One of the complainants, Kate, testified that Slinde called the three girls to her office and questioned them, but dismissed them by saying she didn’t want to hear any more talk about it. According to Kate, Slinde said if they told anyone, even their parents, then Lomnicki would “get in a lot of trouble and go to jail and die.”

Additional allegations surfaced during Lomnicki’s Fountain years involving two fifth-grade girls, one of whom alleged that Lomnicki put pieces of candy into her mouth, and into each of her hands, pulled her shirt tight, and made comments about how her breasts had grown.

Another girl said Lomnicki grabbed her on several occasions, and that he once picked her up by the waist, spit the gum he was chewing into her mouth, and then inserted his tongue into her mouth to retrieve it.

According to their testimony, the girls did not report these incidents to anyone besides Slinde.

Metro Times asked Slinde to respond to these allegations.

“I don’t think I should comment,” she said. “I’m sorry. I have no comment. Goodbye.”

During a deposition in the civil case, Slinde said she thought she had handled the complaints appropriately.

“I felt that it wasn’t necessary to go further,” Slinde testified. “I just felt that there was perhaps a misunderstanding …”

“… I don’t believe it was appropriate for him to do it, but I don’t think it was sexual harassment …”

“… I told Mr. Lomnicki that he was to be very careful and, you know, do no more touching and so on and so forth … he assured me he wouldn’t.”

Slinde said she could not recall if she documented the complaints or her verbal admonishment to Lomnicki in writing. In any case, she said, she destroyed any such records when she retired from the district.

After these incidents, Lomnicki was transferred to Kaiser Elementary in 1979. Kaiser officials were not notified that at least six girls at Fountain had accused him of molesting them, the civil complaint states.

In 1979, Superintendent Mayer was told by the Kaiser principal that four sixth-grade girls were accusing Lomnicki of fondling their breasts. Mayer testified that he investigated the matter and determined that Lomnicki had exercised “poor judgment.”

Asked whether fondling the breasts of young girls would be considered sexual harassment, Mayer said it would depend on how sexual harassment is defined.

“I say it’s undesirable,” he said. “I don’t know what you mean by ‘sexual harassment,’ really.”

Mayer testified that while he determined that the complaints had “no merit,” he placed a written reprimand in Lomnicki’s personnel file, in a sealed envelope, shielding it from anyone but school administrators.

“You are not to straighten clothing or pick up jewelry from beneath a sweater or blouse,” it read, “or to touch students in a way which could be misinterpreted by them or their parents.” Mayer warned Lomnicki that “future instances of poor judgment on your part may result in more severe disciplinary action up to and including discharge.”

Mayer testified that he issued the sealed reprimand “because he occasionally was friendly with students [it] was creating a public relations problem for us, and it had to be stopped.”

Hurwitz asked whether he considered the complaints against Lomnicki a “frivolous claim.”

“No, serious claim, as I indicated. We had a public relations problem,” Mayer responded, adding that he believed the things Lomnicki did were “unintentional on his part.”

And with that, Lomnicki was transferred again, this time to Arbor Elementary, where he was assigned to Chapter I, a federally funded remedial reading program that granted him one-on-one access to students and a private classroom.

In a deposition taken during the civil proceedings, Lomnicki made it clear that the assignment was anything but a punishment.

“In my estimation, it was like a goal that I had [as a teacher],” he said. “I often thought that, gee, I’d like to do that. I think it would be really effective.”

School officials at Arbor were not told that Lomnicki had been accused of molestations at other schools, the civil suit alleges. There apparently were no reported incidents at Arbor for nine years.

Court papers filed by Hurwitz’s team allege that in 1988, six sixth-grade girls told school Principal Roberta Fanti that Lomnicki had inappropriately touched them.

One of the girls, Lisa, testified, “We didn’t call him Mr. Lomnicki. We called him the pervert. I mean, it’s common knowledge from the whole sixth-grade class that that’s what he was.”

Fanti reported the allegations to Leroy Herron, then RCSD’s assistant superintendent under Mayer.

Herron placed a second sealed reprimand in Lomnicki’s personnel file — essentially a rehashing of the one Mayer had given him nine years earlier: “You are not to hug or put your hands on students in a manner that could be misconstrued by them or their parents. If there are any future accusations from students concerning your behavior it could result in further disciplinary action.”

Despite the fact that Lomnicki had already been warned once that further misdeeds could get him fired, neither reprimand led to any “further disciplinary action” by the district.

In fact, the sealed reprimand issued to Lomnicki in 1979 was never referenced in the 1988 sealed reprimand. Asked why, Mayer responded, “I cannot explain.”

Though Mayer determined that there was “no sexual misconduct” in 1988, he did write a letter notifying Child Protective Services of the complaints against Lomnicki. Hurwitz says there is no indication that the agency did any investigation of its own.

“We have no idea what, if anything, they [CPS] did,” Hurwitz says. “We have no idea if the letter was ever sent.”

Lomnicki was shuffled again, this time to Eastland Elementary.

His assignment? The Chapter I reading program.

Jane Doe first encountered Lomnicki in 1992, when she was in kindergarten at Eastland.

In the mediation summary, Jane is described as an “active, energetic and happy-go-lucky child” prior to meeting Lomnicki.

In April 1992, her preschool teacher noted that Jane was articulate, but testing also indicated some immaturity in her development. Two years later, she was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD).

Lomnicki had been teaching at Eastland for several years when Jane began receiving individualized reading instruction from him.

Lomnicki’s alleged behavior with Jane — hanging her on a hook, striking her with a small wooden bat, donning a hockey mask — was the most aggressive and violent reported.

Hurwitz theorizes that Lomnicki was reacting to the pressure he felt from the Warren police’s criminal investigation, which had begun in early 1993.

Jane testified that Lomnicki threatened to kill her if she told anyone about what happened. As a result, she remained quiet.

Outrage

About the time that Jane Doe was alleged to be under Lomnicki’s sway, Wendy, a former Fountain Elementary student who had grown to adulthood, learned that Lomnicki was teaching at Eastland.

In late 1992, an outraged Wendy, who lived in the Eastland area, walked her street, knocking on the doors of families with children and telling them that Lomnicki had abused her when she was his student. One of the people she talked to was Sally Doe, Jane’s mother.

Sally, in turn, asked her daughter whether anyone had inappropriately touched her, but Jane denied anything had ever happened. Unconvinced, Sally went to the school in early 1993 to talk to Principal Susan Enke, who, according to the mediation summary, denied that Lomnicki had abused any of her students.

Enke did know, however, that Warren police had started an investigation of Lomnicki, and she mentioned it to Sally Doe. In spite of the mother’s concern, and the principal’s knowledge of the criminal probe, Enke refused to remove Jane — who would say nothing about what had happened to her for another year — from Lomnicki’s supervision.

The criminal investigation was launched after Sarah K., unbeknownst to Sally or Wendy, went to the police. Nine years had passed since Lomnicki had abused her in her Warren home.

Sarah says she thought she had put the abuse behind her. But then she became a mother. Her new maternal responsibilities triggered a crushing realization.

“Seeing this child who I’m supposed to protect brought memories back,” she says. “It ate me up inside until I did something about it. Then I realized I was doing something for a whole bunch of people.”

She went to the Warren police on Jan. 3, 1993, and told her story to Officer Daniel Klik.

“I am a cynic,” says Klik, who is now a detective. “At that time, I’d been a police officer for 10 years, about. After 10 minutes with a complainant, you realize whether they’re sincere. Sarah was sincere.”

Warren police made RCSD aware of the investigation, which began on Jan. 5, 1993.

Upon learning about it, RCSD attorney Ronald Greve advised Assistant Superintendent Frank Mancina not to freely give Warren police Lomnicki’s personnel file, according to testimony given during the civil trial. Greve did, however, tell Mancina to encourage authorities to get a warrant.

“I advised him to tell the Warren Police Department that, yes, we do have some information, so it wouldn’t be a waste of time getting a search warrant,” Greve testified.

Mayer and Herron had both retired by the time the investigation began.

In spite of these developments, it would be two more months, until March 6, 1993, before new Superintendent John Kment, who is still in that post, took steps to remove Lomnicki from the classroom.

Lomnicki was arrested on March 3, 1993. RCSD administrators then removed and reassigned him to the district’s central administrative office.

The investigation went public in mid-1993 when the Macomb Daily began reporting it. Sarah and Lomnicki were both parishioners at St. John’s Catholic Church, and she recalls the backlash from the congregation.

“They called me names,” she says, “and said things like, ‘You should be ashamed of yourself.’ After the first day of testimony [in the criminal trial], they changed their tune, because they realized it was true.”

Lomnicki was convicted of criminal sexual conduct. He is now serving that sentence and will be eligible for parole on Dec. 1, 2009.

After Jane Doe came forward, a Macomb County prosecutor charged Lomnicki in that case, which was bound over for trial. But after he was convicted and sentenced in the Sarah K. case, the Jane Doe criminal prosecution was dropped to spare the child the ordeal of testifying.

According to Hurwitz, RCSD negotiated a retirement package with Lomnicki prior to his conviction. It provides full pension benefits. Lomnicki retired days before he was convicted.

Timeline

Metro Times wanted to know the defense’s position in pushing the civil proceedings to the brink of litigation, only to give in the day after opening arguments. Most calls to the administrators and district attorneys went unreturned.

Ron Greve was the only one to call back.

“Part of the problem was that the plaintiff started the case in Macomb Circuit Court. We had a trial date, but the plaintiff then dismissed it and refiled it in federal court,” RCSD’s general counsel, Greve, says.

Hurwitz says that when the case was in Macomb County, “We had numerous trial and mediation dates. The defense moved to adjourn all of them. At the end of ’99, we were told by a court-appointed facilitator that the case would never go to trial. We decided the only way we would get a trial date would be to go to federal court.”

Greve says the district said it had no clear evidence that Lomnicki was a pedophile, and didn’t know enough to justify terminating him.

But Dr. Emanuel Tanay, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Wayne State University, had no doubt about Lomnicki’s nature. He viewed him as a textbook pedophile.

“I have a wealth of data indicating that he is a pedophile,” Tanay testified during an October 2003 deposition. “… No psychiatrist will have a choice but to say, yes, Mr. Lomnicki is a pedophile.”

Greve would not comment on the district’s failure to make principals at each school Lomnicki was transferred to aware of past complaints against him.

“I frankly think a lot of these witnesses are saying things that never happened,” Greve says. “I’m not saying they’re lying, but memory is a funny thing.”

Emotional scars

A 1995 psychiatric evaluation linked Jane Doe’s emotional state to her experience with Lomnicki. The report says she had ADHD before meeting him, but she was also said to have acute stress disorder associated with the sexual assault and the criminal proceedings that followed.

Jane Doe’s older sister, Christine, says her sibling experiences nightmares.

Hurwitz says Jane’s emotional state is like that of an 11- or 12-year-old.

Asked why Lomnicki was not removed from the classroom much sooner, Greve said that, because Lomnicki was a tenured teacher, there were questions about whether the district had the authority to suspend him.

Hurwitz says the district had plenty of reason to remove Lomnicki, but she concedes that Lomnicki did benefit from protection provided to educators under the Teacher Tenure Act.

The state law entitles tenured teachers to a full grievance process before they can be terminated, including union representation, and the right to fight reprimands or transfers.

Interestingly, though, Lomnicki never filed any grievances or contested his transfers.

Asked why she pursued the lawsuit so zealously for so long, Hurwitz responds, “When I learned what had happened to this young girl, I felt very strongly that school districts owe a very, very important duty to the students that they are supposed to be protecting, and that it was just so apparent to me that in this case they had so flagrantly failed to protect this child. And the more I got into this case and the more I learned how right I was. And the more I learned how many people had had their lives irreparably damaged by this man and this school district that was set up to allow this man to get away with what he was doing, I just had to stick with it.

“I believe that our civil rights laws are fundamentally important to a system of justice that protects individual people from government abuse, and this was a flagrant example of abuse by a government agency that needed to be addressed.”

Khary Kimani Turner is a Metro Times staff writer. E-mail kturner@metrotimes.com.