Critics of Tallulah say the harsh adult prison-like atmosphere was unlikely to rehabilitate teens.TALLULAH, Louisiana (AP) -- The allegations began soon after the prison opened for business: teenage inmates beaten by guards, beating each other, running loose on the rooftops of the barracks-like dorms.

Ten years later, Louisiana is shutting down its toughest juvenile prison, a move that child welfare advocates see as an admission of failure.

The closing comes after years of investigations -- by the U.S. Justice Department, human rights advocates and others -- called the lockup a place of chaos and brutality.

"Tallulah became known as one of the worst, if not the worst, juvenile facility in the country," said Mark Soler, head of the Youth Law Center, an advocacy group in Washington.

Advocates said the adult-style prison -- with individual cells inside cell blocks behind fences and razor wire -- created an atmosphere unlikely to rehabilitate the teens. They said the teens were more likely to commit far worse crimes when they got out.

A court-appointed expert, after a 1999 inspection, wrote of Tallulah's teen inmates: "If we can't control them and make some difference in their lives now, God help us when we meet them on the street."

The Tallulah prison was part of Louisiana's brief experiment with privately run juvenile lockups. Its clusters of beige metal buildings were built in 1994, with a capacity for 620 inmates. It was used for Louisiana's hard-core juveniles, convicted of homicide, assault, rape and other serious offenses.

The prison, situated in this town of 8,000 in Louisiana's impoverished Delta region, was first run by a management company with no experience in juvenile prisons. Within months, riots and allegations of abuse forced the state to take on-and-off control.

"From the minute it opened, it did the exact opposite of what it was supposed to," said David Utter, head of the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana. "It was a really bad place for kids."

In 1997, the Justice Department found widespread abuse of inmates by guards had left teens with gashes and broken bones. Federal investigators reported a year later that teens were beating and raping fellow inmates.

In response, the state fired hundreds of guards, took over the prison and introduced reforms, including a reduction in the number of prisoners and a process for teens to report violence anonymously.

Through last year, state corrections officials repeatedly said the prison had improved and should remain open.

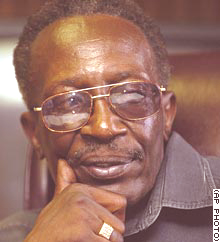

In a recent interview, Hyam F. Guyton Jr., Tallulah's warden since 2001, highlighted the prison's classrooms, its medical facilities and programs for rewarding teens' good behavior. Forms for youths to report wrongdoing were available throughout the complex.

Guyton, a 61-year-old grandfather, said he considered himself a father figure to the inmates, whom he called "my boys." He said they called him "Pop" and came to him with their problems.

Guyton: "I think we did a real good job." "I think we did a real good job, a wonderful job, of correcting those boys' behavior," Guyton said.

Hyam F. Guyton Jr.,

Tallulah's warden since 2001But the prison's end was foreshadowed in 2002, when a Juvenile Court judge cited "grave concerns" for prisoners' physical and mental health and demanded the transfer out of all Tallulah prisoners he had sentenced.

In ordering the closing of Tallulah, state legislators noted last year that Louisiana's juvenile offenders wind up back in prison at a rate of about 60 percent -- far higher than in other states.

"It ended up a brutal place, a demeaning place that made kids angry. And yet, the state continued with this failed experiment for almost 10 years," Utter said.

Fewer than a dozen prisoners remain at Tallulah, down from more than 600 in 1998. By the end of next week, those teens, too, will be transferred to one of Louisiana's three other juvenile lockups -- smaller prisons that never developed a notorious reputation for abuse.

Tallulah will be turned into the type of facility it was modeled after: a prison for adults.

On a recent morning, Guyton peered through his tinted glasses at Tallulah's deserted grounds, the empty basketball courts ringed by razor wire.

"It's like a ghost town here now," he said.