COVER STORY -- Friday, March 2, 2007

Jordan Riak is a self-proclaimed thief.

But not in the conventional way - nobody's missing cars, cash or jewelry.

In fact, the only property that's gone missing is a small thin stick, about the width of bamboo, which was used for whapping elementary school students in the early '80s.

The Alamo activist was living in Sydney, Australia, when he stole a "cane" from his son's principal, as a form of protesting corporal punishment in public schools.

Earlier in the week, his 8-year-old son Justin had narrowly escaped a caning, the process by which students are smacked several times on the hand as a method of discipline. Justin watched as his two close friends came out of the principal's office, one by one, clutching their hands and biting back tears.

"The following day, I kept him home and I went to see the principal. I told him, 'This is a weapon. You have no place striking a child with this, and I'm not giving it back to you,'" Riak recalls.

|

"I told them I'm turning myself in for theft of government property at the police station tomorrow at 4 p.m.," he says.

Sure enough, when it came time, there was a mob of journalists outside the police department. Like a pack of hungry wolves, they crowded around him, flashing photographs and scribbling into their notebooks.

Back then, Riak's goal was to get people talking - to draw attention to the issue. And he succeeded.

Spanking: today's debate

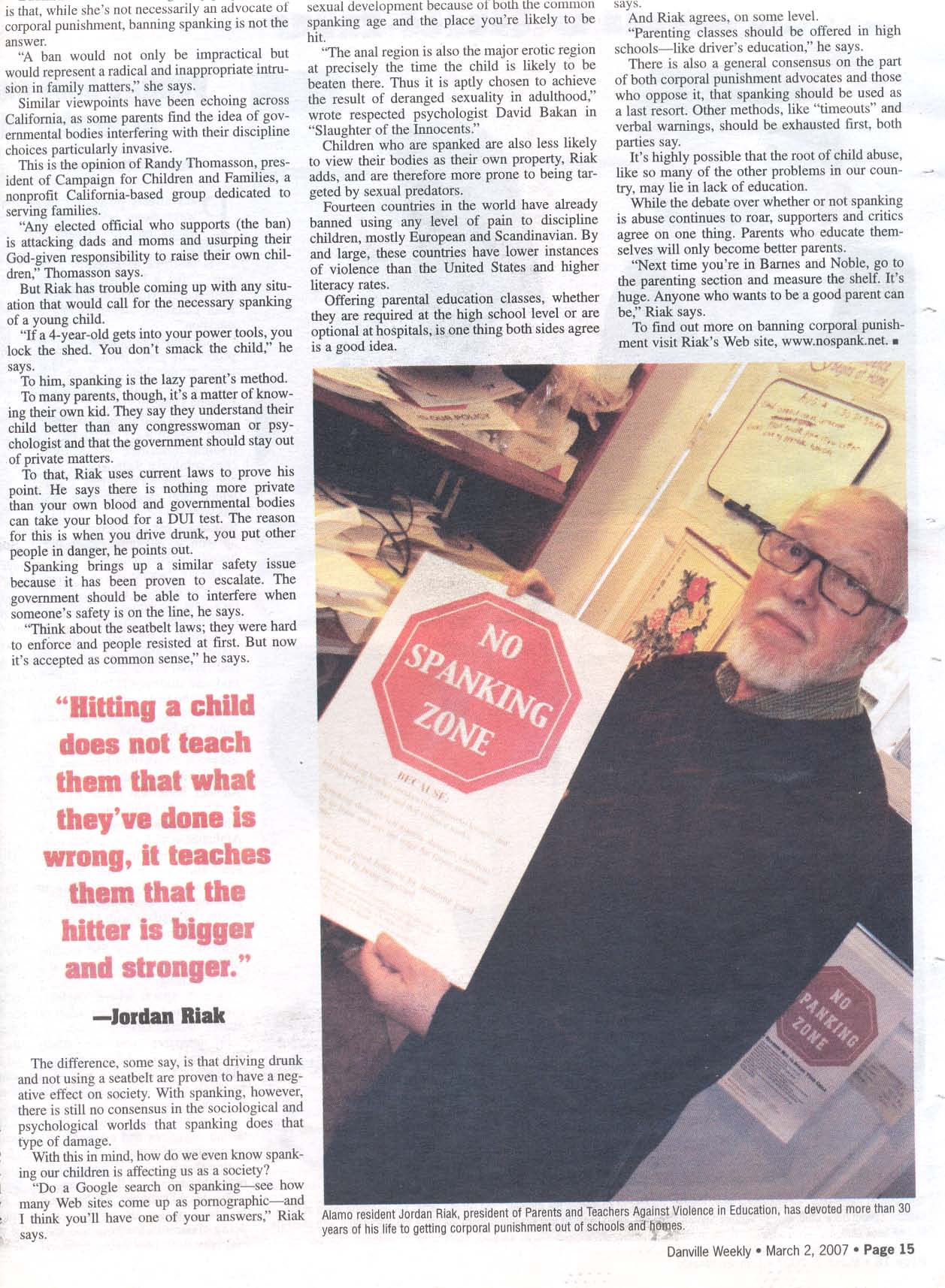

These days, the 71-year-old founder of Parents and Teachers Against Violence in Education isn't stirring up quite as much trouble.

But he is persistently working to get corporal punishment out of the schools and homes in America. Twenty-one states still allow paddling in schools, and the discussion over spanking children at home swept across the country this month, when California Assemblywoman Sally Lieber (D-Mountain View) proposed a bill to criminalize spanking children under the age of 4.

When Riak first moved to Alamo in the early 1980s he drafted California Assembly Bill 1617, legislation to ban pain as punishment in schools.

Since then, his booklet, "Plain Talk About Spanking," has generated national attention from parents, teachers and acclaimed psychologists.

So it's no wonder that this month his e-mail box has been full enough to burst.

"I've gotten a lot of hostile mail," says Riak, with a faded New Jersey accent, over a midmorning conversation at his kitchen table.

In just days, the debate over spanking spread from California, across the country, into national newspapers and onto popular TV news channels. Saturday Night Live even spoofed the issue during its weekend update segment three weeks ago.

Originally, Lieber proposed that the bill criminalize spanking for children under the age of 4, with harshest punishments including a year in jail or up to a $1,000 fine, though Riak says it's silly to think first time offenders would go to jail.

Legislators and activists for children said spanking often escalates into physical and emotionally abusive territory, while those who practice more traditional parenting say it never did them any harm.

Last week, however, the congresswoman redrafted the bill to define what child abuse is - including vigorously shaking a child and closed handed hitting. But this time she left spanking out of the equation. To many advocates of a ban on corporal punishment, leaving out spanking was a big step backward.

Other recent changes to the proposed legislation include adding non-violent parental education classes to the possible penalties, Barry N. Steinhart, principal assistant to Sally Lieber, said last week.

Spanking in Alamo

Not surprisingly, Riak adamantly supported the spanking bill. His view is that spanking a child is not only an ineffective way of disciplining, but that it also causes long-term negative effects to a child's emotional, social and sexual development.

"Hitting a child does not teach them that what they've done is wrong, it teaches them that the hitter is bigger and stronger," he says.

He backs his theory up with social and psychological studies, indicating that children who are spanked are more prone to acting out through aggressive behavior, that spanking is a form of humiliation, and that societies that use corporal punishment are more prone to violence.

In an educated, family-oriented community like Alamo, where Riak raised his children, the common thread is that most parents are committed to learning about and doing what's best for their kids.

Even without a controversial bill, this is something parents should be thinking about, Riak says.

"We are a community that cares about children and we want to be informed if we are doing something that's not good for them," Riak says.

During some of his outings to other East Bay communities, he sometimes hands out stickers to spread the word about why not to spank. The stickers say, "Kid's safe zone. No Spanking."

The way parents respond to him says a lot about how that community treats its kids, he says.

In Alamo, he says most parents are very receptive to his message, while they may or may not completely agree with him. Parents usually let their kids take a sticker and then explain what it says and the meaning behind it.

At grocery stores in Danville and Alamo, Riak has even heard children ask, "Mommy, what is spanking?" But in other places, like Concord for example, he is no stranger to the cold shoulder. The difference in views is vast, he says.

Don't we already have laws against child abuse?

Throughout history, it has been legal to slap slaves, servants, wives and even employees. Today, children are the only group that isn't completely protected.

The problem with existing laws, Riak says, is that most use vague language that helps protect the parent rather than the child.

Nebulous phrases like "reasonable in the circumstances" are commonly found in child abuse protection laws.

This creates a gray area - a slippery slope for clearing abusive parents, he says.

"A favorite alibi for child abusers is 'I was only disciplining.' One person's idea of reasonable is very different from another's," he says.

But mild spanking, many parents say, is necessary - whether to straighten out a defiant youngster or to quickly teach them about danger.

One recent study supports the notion that a little swat doesn't do kids any real harm.

Dr. Diana Baumrind, a psychologist from UC Berkeley, conducted a study in 2001 that demonstrated no negative social or developmental effects result from mild spanking. Her case study included about 100 parents and families in the Bay Area.

The critics

Baumrind's take on the orginally proposed bill is that, while she's not necessarily an advocate of corporal punishment, banning spanking is not the answer.

"A ban would not only be impractical but would represent a radical and inappropriate intrusion in family matters," she says.

Similar viewpoints have been echoing across California, as some parents find the idea of governmental bodies interfering with their discipline choices particularly invasive.

This is the opinion of Randy Thomasson, president of Campaign for Children and Families, a nonprofit California-based group dedicated to serving families.

"Any elected official who supports (the ban) is attacking dads and moms and usurping their God-given responsibility to raise their own children," Thomasson says.

But Riak has trouble coming up with any situation that would call for the necessary spanking of a young child.

"If a 4-year-old gets into your power tools, you lock the shed. You don't smack the child," he says.

To him, spanking is the lazy parent's method.

To many parents, though, it's a matter of knowing their own kid. They say they understand their child better than any congresswoman or psychologist and that the government should stay out of private matters.

To that, Riak uses current laws to prove his point. He says there is nothing more private than your own blood and governmental bodies can take your blood for a DUI test. The reason for this is that when you drive drunk, you put other people in danger, he points out.

Spanking brings up a similar safety issue because it has been proven to escalate. The government should be able to interfere when someone's safety is on the line, he says.

"Think about the seatbelt laws; they were hard to enforce and people resisted at first. But now it's accepted as common sense," he says.

The difference, some say, is that driving drunk and not using a seatbelt are proven to have a negative effect on society. With spanking, however, there is still no consensus in the sociological and psychological worlds that spanking does that type of damage.

With this in mind, how do we even know spanking our children is affecting us as a society?

"Do a Google search on spanking - see how many Web sites come up as pornographic - and I think you'll have one of you answers," Riak says.

Spanking, sexuality and education

As the theory goes, being spanked affects your sexual development because of both the common spanking age and the place you're likely to be hit.

"The anal region is also the major erotic region at precisely the time the child is likely to be beaten there. Thus it is aptly chosen to achieve the result of deranged sexuality in adulthood," wrote respected psychologist David Bakan in "Slaughter of the Innocents."

Children who are spanked are also less likely to view their bodies as their own property, Riak adds, and are therefore more prone to being targeted by sexual predators.

Fourteen countries in the world have already banned using any level of pain to discipline children, mostly European and Scandinavian. By and large, these countries have lower instances of violence than the United States and higher literacy rates.

Offering parental education classes, whether they are required at the high school level or are optional at hospitals, is one thing both sides agree is a good idea.

"Education, not legislation, is the method of choice to improve parenting practices," Baumrind says.

And Riak agrees, on some level.

"Parenting classes should be offered in high schools - like driver's education," he says.

There is also a general consensus on the part of both corporal punishment advocates and those who oppose it, that spanking should be used as a last resort. Other methods, like "timeouts" and verbal warnings, should be exhausted first, both parties say.

It's highly possible that the root of child abuse, like so many of the other problems in our country, may lie in lack of education.

While the debate over whether or not spanking is abuse continues to roar, supporters and critics agree on one thing. Parents who educate themselves will only become better parents.

"Next time you're in Barnes and Noble, go to the parenting section and measure the shelf. It's huge. Anyone who wants to be a good parent can be," Riak says.

To find out more on banning corporal punishment visit Riak's Web site, www.nospank.net.