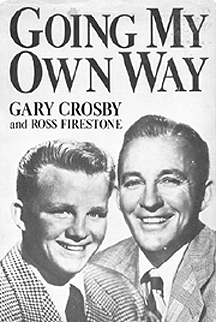

"In a way, I did understand why Dad's fans loved him so. When I saw Going My Way I was as moved as they were by the character he played. Father O'Malley handled that gang of young hooligans in his parish with such kindness and wisdom that I thought he was wonderful too. Instead of coming down hard on the kids and withdrawing his affection, he forgave them their misdeeds, took them to the ball game and picture show, taught them how to sing. By the last reel, the sheer persistence of his goodness had transformed even the worst of them into solid citizens. Then the lights came on and the movie was over. All the way back to the house I thought about the difference between the person up there on the screen and the one I knew at home." Gary Crosby

I hated being in trouble. I was in it all the time. It's just about the earliest memory I have. Mom and Dad had gone out for the evening, leaving us in the care of our keepers. I was six. Denny and Phil were five. Linny was still an infant and probably asleep in his crib. We should have been sleeping, too, but had kept ourselves awake whispering in the dark from our beds. It was risky -- this was a whipping violation -- but the danger made it exciting and the excitement was hard to resist.

I suppose that's why we plunged ahead when our thoughts turned to the canary down the hall in Mom's dressing room. We knew we weren't supposed to leave our beds but agreed we just had to pay it a visit anyhow. Taking care to muffle the giggles that might rouse our nurse, we crept down the long corridor to Mom and Dad's wing of the house, eased open the door and peered inside. The bird was chirping away in its cage.

We stood there in silence, watching it sing to itself on the other side of the doorway. But then the twins grew restless. They wanted more. They wanted to touch the canary and pet it. The caper was getting out of control. We were never to set foot in that part of the house by ourselves. It was bad enough to be up past our bedtime and out of our room.

"Don't go in there!" I hissed, hoping to scare some sense into them. "Holy smoke, don't go in there! They'll kill us!"

But my brothers weren't as terrified of them as I was -- yet.

"Oh, come on, they'll never find out."

That sounded crazy to me.

"What do you mean, they'll never find out? They'll be sure to know. They'll see the footprints in the rug. They know everything."

"No they won't!"

Laughing together, they bounded across the threshold into forbidden territory. I stayed where I was, making sure to keep my feet away from the edge of Mom's white carpet, and watched them head straight for the cage. It was too high to reach, but that didn't stop them. They scampered up the back of the divan next to the stand and in a moment had the little door unfastened. One of them reached in his hand for the bird. It got to fluttering and squawking. Then suddenly it was silent.

I streaked back to my room and threw myself into bed. They were right behind me. "Oh my God, what did you guys do? What happened?" "I don't know," Denny sobbed. "I guess we killed it."

We tried to stay awake until Mom and Dad came home but drifted off to sleep. Sometime in the middle of the night the nurse woke us up. She got right to the point. "Your mother and father want to see you."

I was the first to be called in.

They were in Dad's office next to their bedroom. Mom was standing with her arms folded. He was sitting behind his desk.

"What's this?" he asked, pointing to the tiny dead thing on the top of the desk. "Who was in here? You're the oldest. Why didn't you take care of your brothers?"

I had nothing to say. It wouldn't do any good to tell him we hadn't meant to harm the bird. It would be better to stay silent and just take it. I knew I was going to get it. The only question was whether it would be from the back of Mom's silver hair- brush or from Dad's hands.

I remember his hands very well. They were short and stubby, not muscular but extremely strong. That night it was their turn. When he was through, he sent me back to my room and hollered out the door for the next one.

"Philip, you get in here!"

I read the fear on Phil's face when I passed him in the hall. Denny was sitting on the edge of his bed, staring down at the floor, waiting to get it next. When it was finally over, each of us retreated into separate corners of the room to let out our tears in . private. Then we pulled ourselves together and went back to sleep.

They didn't speak to us the next morning. The silence lasted the rest of the week. About all they had to say was, "Watch your step. Just watch your step now." We had to be especially careful after we got it because then their eyes never left us. They scrutinized every move we made, and it didn't take much to get it again.

Even after life returned to normal we had to keep a close watch on our actions. We could still get it at any time. All the servants were allowed to take a shot at us. The other help never did, but we had to walk softly around our nurse. If she thought we were stepping out of line, she was free to whip us or do whatever else she dreamed up. Sometimes the punishment got out of hand.

One nurse liked to use the drowning treatment. If she caught, any of us talking in bed or getting up too early in the morning, she hustled the guilty party into the bathroom and ordered him into the tub. When it was filled with two feet of water, she grabbed him by the hair, plunged his head down to the bottom and held it there awhile, then brought it back up so his face went under the stream still gushing from the faucet. If you timed it right, you might catch a short breath between the faucet and the tub.

It never occurred to us to complain. We assumed the grownups were all in it together. There didn't seem much point in telling one adult what another was doing to you. You might even make things worse. I was more surprised than relieved when Mom happened to walk into the bathroom one morning and caught the nurse in the middle of her routine. She exploded in rage. If she could have gotten her hands on a knife or gun, I'm quite certain she would have killed the woman. As it was, she fired her on the spot and threw her out of the house.

We had so many rules to follow, it was hard not to do something wrong. Just about every waking moment was controlled by its own set of regulations.

There was a rule about not talking to each other after we went to bed at night and before we got up in the morning. Someone usually checked to make sure we obeyed. When Georgie took over as our nurse when I was eight, that became her special passion. She would set her alarm clock half an hour early, then hover outside our door so she could catch the first words of the morning tumble out of our mouths when we awoke. At the opening whisper, she came roaring in, ripped off the covers and whaled on us with a wire coat hanger. Later on she would tell Mom and, depending on her mood that morning, she might let us have it again. That's how we started our day.

There were rules about brushing our teeth, showering, making our beds, straightening our room. If the toothbrush wasn't wet or the towel felt dry, that was good for a punishment. So was not hitting the breakfast table at the right time or not dressing the right way. When one of us left a sneaker or pair of underpants lying around, he had to tie the offending object on a string and wear it around his neck until he went off to bed that night. Dad called it "the Crosby lavalier." At the time the humor of the name escaped me.

At breakfast there was a rule about finishing everything on our plates. Phil was a picky eater and had his problems with that one. But a rule was a rule. There were no exceptions. The morning he tried to get around it by hiding his bacon and eggs, Mom discovered the bulge under the rug and made him scoop the mess back onto his dish, then choke down every bite -- dirt, hairs and all.

When the chauffeur drove us off to school, there was no wrestling or fooling around in the car. Nor was he to be kept waiting when he came to pick us up in the afternoon. If one of us dawdled on the way to the parking lot, Mom knew because she had the trip timed down to the minute, and he would get it as soon as he walked in the door.

In school we were expected to be model students. God help us if the teacher called home with a complaint or made one of us stay late for misbehaving. That was a certain whipping. We were also in big trouble if our grades weren't mostly A's and B's. A D got a licking. An F meant a licking and having to sit in the room with your books every afternoon for the next month until the new report card came home. A C, especially in conduct or effort, brought a loss of privileges and intimations of worse things to come if you didn't clean up your act on the spot. "Jesus," Dad would grumble, "can't you get anything better than a C? What the hell are you doing in there? Watch it. Just watch it, that's all."

If we played in our rooms before dinner, the door had to remain open so the grownups could listen in and see what we were up to. I didn't understand why, but it seemed to make them uneasy if we became too quiet. Of course, we couldn't be too noisy either.

Dinner was accompanied by a whole slew of rules. It was served formally in the dining room, with the table laid out in a hopelessly confusing array of plates and silverware. Mom studied us closely while we ate to make sure we used them correctly. We sat up straight on the edges of our chairs, with our elbows in at our sides and the forks held in our left hands so we could cut everything properly in the European fashion. If one of us picked up the wrong spoon or put the butter in the wrong dish, she reached over with the butt of her knife and gave him a whack on the knuckles. Dad didn't seem to take Mom's rage for good table manners all that seriously. He liked to pretend he didn't know which spoons to use either. Sometimes he deliberately irritated her sense of decorum by wolfing down his food with his mouth wide open. But that was between the two of them. We minded our own business and did what she told us. Still, there was always that devil in my brain who kept asking, "How come that's okay for him but not for us?"

The meal passed mostly in silence. They didn't have much to say to each other, and unless one of them asked us something, we weren't allowed to speak until we finished eating. There were usually one or two perfunctory questions about school, which we answered in the fewest possible words.

"So how was school today?"

"Okay."

"What did you do?"

"Went to class and played ball at recess."

Dinner seemed to take forever. It was finally over when Dad cocked back his chair, wiped his mouth, threw his napkin in the middle of his plate and said, "All right, you boys may be excused." That was the signal we were free to head upstairs to do our homework and go to bed.

I tried my best to toe the mark each day and hit all their rules and regulations. Not so much because I hoped to please them and win their approval. That seemed too far out of reach to consider as a serious possibility. It was more a matter of wanting to steer clear of the lickings and other punishments that followed fast behind their disapproval.

There was also the hope of gaining some favor at the end of the week. The lure was hard to resist, even though the chance of staying in their good graces was remote. I still remember the time the four of us asked if we could postpone our Saturday-morning chores and go to the Hitching Post theater on Hollywood Boulevard. We had heard about the place at school. The kids lined up at 8 A.M. in their cowboy outfits, checked their cap pistols on the wall, then settled in for a nonstop marathon of Westerns, serials and cartoons that lasted until four in the afternoon.

We bided our time until they both seemed in a decent mood, then worked up the nerve to make our pitch. "Um, do you think we could go to the Hitching Post this Saturday?"

"Why, sure you can," they answered. "Just don't do anything wrong the rest of the week."

We knew what that meant. When we went back upstairs, we told each other, "Well, that's the end of that. It's a cinch there's gonna be something wrong by Friday." And, of course, there was.

It didn't help much when, on the spur of the moment Saturday .morning, Mom decided that even though we had been bad she would have her friend Irma Thayer take us to The Mikado. Irma was a nice lady and we didn't want to hurt her feelings, so we pretended to enjoy it. But as I sat there watching the people onstage run around and holler in a language that seemed to be English but made absolutely no sense, all I could think was, "When will I get to do what I like? Why is what's good for me always what I hate?

As much as I tried to give them what they wanted, there were things about myself I couldn't seem to change or even control. One of them was my weight. From the time I was just a few years old I had a big, wide behind, and the rest of me was built like a fire hydrant. I looked like a lard bucket. Maybe because he had to struggle with his own weight problem, the old man was determined to make me slim down. He had me exercise. He put me on a diet of grapefruit and celery. When that didn't do the job, he concocted putdown nicknames that were intended, I suppose, to fuel my motivation.The name-calling started early. It shows up in a 1937 interview he did at Paramount on a day he happened to take me with him. The clipping tells the story. I was four.

"Gary Evan is named after his daddy's pal, Gary Cooper. Bing recently brought Gary Evan down to Paramount to visit his namesake on the Souls at Sea set, and the tall, serious Cooper engaged the knee-high lad in conversation.

"'So we have the same first name, have we?' mused Cooper. Well, my folks call me Frank. That was my name before the studio changed it for Gary. What does your daddy call you?'

"Bashful Gary dug the toe of one scuffed sandal against the side of the other and answered,

"'Bucket Britches.'"

I guess Dad's fans thought "Bucket Britches" was cute. It didn't seem cute to me. Neither did "Satchel Ass" or "Bucket Butt" or "My Fat-assed Kid." That's how he introduced me to his cronies when he dragged me along to the studio or racetrack.

I remember tagging behind him at the track early one morning when I was about five. I was hanging in the background watching the sun rise and the steam spill out of the horses' nostrils, when some of his pals appeared and he snapped me out of my reverie.

"Hey, Bucket Butt, get over here! ...Okay, this is Satchel Ass. Meet My Fat-assed Kid." They laughed and enjoyed his little joke with him. All it did for me was make me hurt and angry and leave me just as hungry as ever. Even then I was too afraid of him to let him see how I felt, so I tried to keep it hidden. But I wasn't a good enough actor yet. When he caught the scowl flicker across my face, he busted me on it immediately.

"Hey, what's the matter with you? Something wrong?"

"Nothin', Dad. Nothin'. Everything's fine."

"Good. Okay, then. Come on, Bucket Butt. Let's go. Move it."

The older I grew, the more of an issue my weight became. Anytime he could catch me up on it, he would. If he heard that I failed to beat out a bunt in a baseball game at school or just missed being safe at first on a grounder, he would say, "Well, if you were thinner, if you didn't have so damn much lard on you, you'd have made it." Even when I didn't mess up, he found a way to throw in a barb: "Denny says you got off a thirty-yard run yesterday. Not bad. Bet you could have gone for a touchdown if you dropped twenty pounds."

By the time I was ten or eleven he had stepped up his campaign by adding lickings to the regimen. Each Tuesday afternoon he weighed me in, and if the scale read more than it should have, he ordered me into his office and had me drop my trousers.

It didn't take a whole lot of thinking to realize this was never going to end unless I stuck religiously to the grapefruit and celery, until I finally slimmed down to his satisfaction. I couldn't do it. I could get by without the bread and potatoes. That wasn't too bad. But my craving for sweets couldn't be denied. I had to have something sweet to eat. Just had to. And since he wouldn't give it to me, I learned to take it for myself.

If I couldn't cajole Wilma into slipping me a handful of cookies or a slice of pie, I sneaked into the kitchen when she wasn't looking and stole them. I filched chocolates from the box in the living room sideboard. I became quite adept at it. I would take four or five pieces at a time, and no one could tell they were missing. To cover my traces, I made certain not to leave any empty papers in the box and moved around the remaining pieces to close up the telltale spaces. I spirited the stolen treasures upstairs and hid them behind the bedpost, then waited until later that night, when I was sure Georgie and my brothers were asleep, before I devoured them. The next morning I folded the papers and arranged them carefully in my pants pocket so they didn't form a bulge. When I got to school I slipped them into the trash can.

I wasn't trying to be defiant or flirt with danger. I hated flirting with danger. It terrified me. But I couldn't seem to stop. I thought I was insane. I would plead with myself: "You know if you don't lose weight he's gonna whip you. Are you crazy?"

But then I would think about the cherry pie in the pantry or that box of candy sitting in the living room. Every school day I had to leave the house an hour early and walk towards school as fast and as far as I could, until the car came along and picked me up. That night Dad was told how far I made it. To prepare myself for the Tuesday weigh-in, I stopped stealing food on Sunday and began swiping milk of magnesia from the medicine cabinet in the bathroom. Monday morning I weighed myself, and if I was still a pound or two over I stepped up the dosage and didn't eat the rest of the day. Instead of going to the lunchroom, I put on a heavy sweater or sweatshirt and jogged around the track for an hour, hoping to burn off some calories that way. Monday night I took more milk of magnesia and still more Tuesday morning. I spent most of Tuesday on the school toilet. If I was lucky, when I stepped on the scale late Tuesday afternoon the needle wavered just under the magic number and, all thanks to God, I was safe again for another week. But a lot of times I didn't make it. And whether I made it or not, I'd start shoving the sugar in my face again Wednesday morning and be right back on the same terror trip the following Sunday.

I worried almost as much about school. Part of the problem was my grades. I did all right in languages and history, but once we moved into fractions I was a basket case in math. It seemed hopelessly beyond my comprehension. "You've gotta figure this out," I would lecture myself as I tried to decipher the homework assignment. "The test is coming up, dummy, and you have to pull a B or C somehow."

The sensible move would have been to ask the teacher for help. I thought about it but never did. If I admitted I was already in trouble, she would mail off a note to Mom and Dad and they might start in on me even before the grades came home. At the same time, I knew the report card better not show up with any D's or Fs. There didn't seem a way out of the bind, so I resigned myself to the prospect of getting my ass whipped every month. Sometimes I managed to scrape by, but that's usually what happened.

After the lecture and whipping I would have to forget football or baseball practice for the month and sit in my room with the math book every afternoon until the next report card. It didn't matter whether or not an assignment was due. "All right," Dad would tell me as I pulled up my pants and he returned the belt to his closet, "you go in that room with that book, and you stay there until you get a better grade. That's it." Mom tacked on the same punishment whenever I brought home a bad mark in deportment. If I finished my homework early, she would think up extra math assignments to keep me busy without really knowing what she was asking me to do.

"Done already? Well, read the next fifty pages, then write down for me what they're about."

But my biggest problem in school was my conduct. When I was seven or eight I discovered that if I said something funny the boys in class laughed and that meant they liked me, they were on my side. That was important to me then. If I was supposed to be one of the guys, then I wanted to be one of the guys, and humor seemed to make that possible. It saved me a lot of aggravation that came with being Crosby's kid. It earned me their acceptance.

I couldn't get that by being a good student. I remember how cautious I was about raising my hand when the teacher asked a question and I had the answer. If I did it too often, the guys let me know by their looks that I was being a smartass, and later on in the school yard they steered clear of me. So I spaced my answers out to no more than one or two a week and restricted them to subjects where I was doing poorly and needed the points. And God help me if the teacher seemed to like me. Then the kids really made my life miserable. It was better to be the class clown. I knew the risks, but if I saw an opportunity to make something funny happen I took it. I would whistle between my teeth without moving my lips, then glance around in bewilderment when the teacher tried to detect who was disrupting her lesson. I mugged and grimaced when she turned her back. I passed notes to my fellow conspirators and used my delivery to turn it into a comedy routine when I was caught red-handed.

"Crosby, are you passing a note?"

"Oh, no, Sister, not me."

"Well, what's that piece of paper doing in your hand?"

"What piece of paper? . . . Oh, my goodness, look at that. How in the world did it get there?"

I ran my mouth when I should have been listening, then played out the scene when the teacher called me on it.

"You talking, Crosby?"

"No, Sister, I wasn't talking."

"Then what were you doing?"

"Well, I was sayin' my prayers."

"Saying your prayers in the middle of class?"

"Yes, Sister. Y'see, I forgot them this morning, and when I remembered I thought I'd better say 'em now."

"Well, now is not the time."

"Yes, Sister."

When I discovered I could make the kids laugh I got to liking it and wanted to do it all the time. I realized, of course, I would have to pay the dues. They might give me a big hand for keeping them entertained in arithmetic, but they weren't going to be around later when the score was settled at home. I wasn't a glutton for punishment, so I tried to hold myself in check. Nine times out of ten I managed to choke off the wisecrack as it leapt from my throat. But then there was the tenth time. I would have myself under control for a while and start to relax, when I caught some kid's eye across the room and said or did something stupid that was bound to cause me grief.

It was like walking the razor's edge. I had to tone down my antics so they weren't offensive to the teacher but still got the desired yucks. The A-Move was to make the teachers laugh too. Then they couldn't keep me after school and start off the chain of punishments. But their tolerance level varied. One day the Sister might crack up with the rest of the class when I wised off, and later that week she might be allover me like white on rice. So it was always chancy.

When I was due for a licking Mom sent me outside to pull a '" switch off a tree in the backyard. I had to be sure to make the right choice. The branch couldn't be dead. It had to be limber, with plenty of spring still in it. She examined it carefully when I brought it upstairs to her room, then had me roll up my pants and bend over.

"Okay, don't move. And don't cry. And don't reach back with your hands. You just stay there and take it till I'm finished with you."

Then she went to work with the switch, cutting up and down the backs of my legs as fast as she could get her arm to move. It was hard to stay still. My legs felt like they had caught fire or were being jolted by a thousand volts of electricity. But if I jumped out of the way she turned into a crazy woman and whacked me even harder. "Don't you move! Didn't I tell you not to move! Now you're really gonna get it!"

After a while I learned how to hold myself motionless until she ran out of steam and sent me off to my room. If Dad wasn't away on location, she might offer me a choice. "Do you want it from me or do you want it from him?"

My answer was always the same.

"I'll take it from you, Mom. I'd rather have it from you."

It wasn't that she hurt less, but she was there on the spot and he wouldn't be back until six. I hated the waiting almost as much as the whipping and wanted to get it over with as quickly as possible.

When it was the old man's turn, I waited in my room listening to the quarter hours go by on the U.C.L.A. clock over in Westwood. The clock played a tune each time it struck the hour. Every fifteen minutes it performed a different portion of the tune. The closer to six it moved, the longer it seemed to take to get from one part of the melody to the next. By five-thirty time seemed to have dragged to a standstill, and my stomach was coiled as tight as the mainspring. It was practically a relief when the front door slammed closed and he was finally home. A few minutes later I would hear his voice calling from down the end of the hall.

"Gary! Get in here!"

When I came into his office he would be sitting behind his desk. He would look up with those icy-blue agates, then begin the lecture that preceded the whipping. He would be angry, but it was anger from on high, cold and dispassionate and contained, like that of a judge passing sentence on a culprit beneath his contempt.

"Your mother tells me you shot your mouth off in school again today."

"Yes, Dad."

"Well, why do you act like that? Why do you do these things?"

"I don't know, Dad."

"What do you mean you don't know? You must have a reason."

"I don't know. I just don't know, Dad."

It wasn't much of an answer, but that's all I had to say. I learned early that no reason would be good enough to get me out of the licking, so what was the point of trying to explain? Whenever I had, he cut me off before the words left my mouth: "Well, Dad, I think -" "Don't think," he would snap back. "You can't think anyway." It didn't pay to argue with him.

"You don't know, huh? Well, then you're either stupid or rebellious or just plain crazy. I don't know what it is with you. Your mother and I lay down certain rules very simply. All you have to do is follow them."

Then he would launch into three-syllable words and fancy phrases I couldn't understand, though their drift was clear enough. His point seemed to be that the particular outrage I had committed that day was only indicative of all the other things that were wrong with me. So it wasn't just my big mouth. It was also my weight and my temper and the fact that I couldn't get along with people and wasn't smart enough to handle anything but manual labor.

". ..So if you don't alter your behavior, all you're gonna do is grow up to be a fat, stupid, bad-tempered individual that no one will like or want to have around. If that's what you want to be, just continue the way you're going. Because that's what you're headed for."

I usually tuned him out by the middle of the harangue. I had heard it before and was thinking about the beating that would be coming up next. Yet as I stood there in front of him, I would nod in the right places and say yes or no precisely on cue, so that I seemed to be sucking in every word. Eventually he was ready to get to the main event.

"Okay, take 'em down."

I dropped my pants, pulled down my undershorts and bent over. Then he went at it with the belt dotted with metal studs he kept reserved for the occasion. Quite dispassionately, without the least display of emotion or loss of self-control, he whacked away until he drew the first drop of blood, and then he stopped. It normally took between twelve and fifteen strokes. As they came down I counted them off one by one and hoped I would bleed early. To keep my mind off the hurt, I would conjure up different schemes to get back at him, ways to murder him. They had to be perfect crimes so I wouldn't be caught. Maybe I could poison his coffee or "accidentally" bump him out his office window.

I was forbidden to cry or scream, so I had to hold myself together until he cut me loose and sent me back to my room. Then I went berserk. The same red veil of rage descended as when I brawled in the school yard, and I pummeled my fists against the door or the walls or anything else I could smack hard without breaking. I did have to be careful of that. If something broke, I'd be in even bigger trouble. To play it safe, I might run outdoors to the far side of the grounds and pound against a tree or the sides of the garage. If Dad heard the racket, he didn't mention it, but I suppose that's where his criticism of my temper came from. I certainly wouldn't let him see it face to face.

When my anger finally died down, I tried coming to terms with what had happened. The lectures must have sunk in more than I thought. My mind always played back the same tape.

"Jesus, I'll never get anything right. I'll never do anything worth a shit. I'll never be any good."

I didn't believe I could ever stop doing the things that were getting me whipped. I couldn't envision myself earning all A's and B's or holding down my weight or guarding my mouth twenty-four hours a day for the rest of my life. I might for a while, but then, when no one came down on my head and I started loosening up, there I would go, slipping back into my old bad habits again. I didn't see how I could control it. I didn't see how I could live up to what he wanted.

I suppose that when he kept warning me against being a certain way I felt he was saying that's how I already was. I didn't want to be like that. It was something I couldn't understand, couldn't control, couldn't change. If I knew how to fight it, I would have. Gladly. If some wise man had confided, "Okay, kid, this is what you do: Stand on your head in the comer for thirty minutes a day and you won't be that way anymore," I would have headed straight for the comer and practiced standing on my head. I would have done anything. But since I didn't know what to do, I felt I had to face up to the unpleasant fact that this is how I was and how I was going to remain.

There was no easy forgiveness after a whipping. Dad stayed cold and remote and grew very quiet when I came in his sight. His gaze followed me closely, scrutinizing every move to catch me up when I stepped out of line. And he made it clear that the punishment could happen again at any moment.

"So don't get wise," he would warn. "And don't answer back. Now that you've had the whipping, don't pull something cute or stage some kind of rebellion. Just be quiet and do what you're told."

I had to be especially careful around Mom when she wasn't feeling well.

"Gary, go clean up the yard."

"Yes, Mom."

"What's the matter? You don't like it? What's that tone of voice? What does that mean?"

If my eyes flashed in anger, I might trigger the whole thing off again.

"Don't you give me that look! Watch it now! You know what'll happen to you!"

And if I wasn't careful it would. The only way to get through safely was to keep a tight rein on my feelings and poker-face whatever either of them had to tell me.

"Yes, Mom. Okay."

"Right, Dad. Anything you say."

The twins were a year behind me in school and had a chance to profit from my mistakes. Seeing the grief I brought on myself by shooting off my mouth, they stayed a lot quieter, kept their heads down and did what they could to blend into the crowd. Phil especially didn't want to take any chances. Denny was a bit of a clown in class but never truly offensive. Most of the teachers adored him. He was a naturally likable, freckle-faced little kid who looked like Andy Hardy. Still, we all lived under the same rule of law at home, and they endured their share of terror. Denny's heaviest burden was his grades. He was so full of ebullience and energy that he couldn't sit still long enough to stay connected to the teacher. It probably had something to do with his stuttering. That began when he was about eight and was made to keep his left hand in his pocket all the time. He had a tendency to be left-handed, and Mom and Dad thought that would cure it. Dad dealt with Denny's bad marks by laying on the lectures and lickings each month when the report card came home. Somewhere along the line he also took to calling him "Stupid." His other favorite nickname, which I don't comprehend to this day, was "Ugly." Denny tried to avoid the old man's displeasure by staying out of his way. But he didn't know how to duck, so most of the time he took the brunt of Dad's sarcasm head on. It was easy to see how much "Ugly" and "Stupid" smarted. Denny was such an open child that anyone could read him. When he was happy, you knew it. When he was troubled or frightened, you knew it. He had the map of Ireland on his face. He hardly ever lied. If I cooked up a story to get us out of a jam, he broke down before the interrogation even began. I would rehearse him carefully, then spin out my tale while he stood by in silence. Dad might listen skeptically for a moment, but when he turned to Denny and asked, "Well, is that truer Denny would bawl, "No-o-o-o!" and burst into tears. He was a good, straight, honest kid.

Mom was too loyal a wife to question anything Dad did, but when she saw how the put-downs were making Denny feel about himself, she went out of her way to build up his ego. She showered him with hugs and kisses. She called him into her room and sat him down on the bed for frequent pep talks.

"You're not ugly. You're handsome. You're not stupid either. And you're the best athlete of the bunch. You're terrific. So don't pay attention to that stuff. Your father doesn't mean it. He's just kidding."

I couldn't understand why the old man didn't ease up on the name-calling when he saw how much we loathed it. Maybe, like Mom said, he was only kidding around. But that's not how it felt at the other end. It just wasn't the same as when he kidded around with Bob Hope in his dressing room at Paramount. They were equals. If he called Hope "Ski Nose," Hope could snap back with "Hippy," and they both got off on the humor and affection behind the insult. But Denny and I were his children. We couldn't do the comeback. We could only stand there and take it.

In the long run Mom's efforts with Denny worked a world of good. He lapped up her praises like a hungry puppy, and by the time he reached his teens he felt equal to anyone. Until Mom died he had more self-confidence than the rest of us put together.

Phil lucked out with the nicknames "Dude" and "Handsome." Dad began using them when Phil was seven or eight and took to standing forever in front of the mirror combing his blond, curly hair into a pompadour. Once he set it up just so, it was war if any of us messed with it. Phil was fastidious about his appearance at an age when most kids couldn't care less, so at first the names had a certain caustic edge. But after a while they lost their original sarcasm and only served to reinforce his ego. They worked out nicely for him.

When I was four and a half my youngest brother, Lindsay, was born. Linny was the only one of us with brown eyes. He differed in other ways as well. He was a quiet, dreamy, unaggressive child who read a lot, got good marks in school and liked to draw and paint.

The quality I recall best was his vulnerability. It's the common thread running through most of the early memories I have of him. There was the time he devoured a handful of red berries from a bush in the backyard and went into convulsions. He would have died if Mom hadn't sped him off to the hospital to have his stomach pumped. As a toddler he wore a perpetual knob in the middle of his brow from falling down and striking his head on the ground. Until he grew taller, his head was much too large for his body and he was forever losing his balance. His earliest nickname was "The Head," because when he came swaying down the street that's about all you saw of him.

Linny's greatest vulnerability came from being Dad's favorite. Maybe because he was the baby of the bunch, the old man seemed to determine his preference as soon as he came along. Less than three months after Linny was born, he told an interviewer,

"Gary and the twins will probably grow up to be housewreckers. They wreck everything they can get their hands on now. But Lindsay may amount to something. He's the quietest kid I ever saw."

My brothers and I were acutely aware of how Dad felt. We watched the two of them closely and saw that he never called Linny names and never made fun of him. He didn't seem to get as angry when Linny was bad and didn't whip him nearly as much. The reason may simply have been that Linny caused him less bother. He was a good kid. But, to our way of thinking, that didn't justify the favoritism and special treatment. Linny was some four years younger than us -- a huge difference to a child -- yet he was allowed to stay up as late, received the same allowance, got to go everywhere we went and was awarded the same privileges without having to work for them. They were just handed to him, like the special trips Dad took him on. It seems so trivial now, but the three of us were like cons in a prison who would take a knife to another inmate for scoring an extra cigarette.

Whenever Dad went off for a few weeks, Linny was left alone in enemy camp and we were free to vent our resentment. We flipped him on the back of the head as we sprinted past. We pushed him around during the games in the backyard. Most of all, we ragged him with our mouths.

"Hey, Kiss Ass, always sucking up to Daddy. Daddy's Little Boy. Daddy's Favorite. Daddy's Little Angel, who never does anything wrong. The Little King is perfect."

Linny didn't know what to do about it. None of it was his fault. He hadn't bothered or hurt anyone. When we started in on him, he just stared back in confusion with those big brown eyes of his. That's what I remember best. Those big brown eyes looking around, watching in quiet.

We had our disagreements and differences, as any four brothers will, especially when they are almost constantly in each other's faces, but we tried to take care of them ourselves without bringing in Mom and Dad and our other wardens. What kept us united was our common enemies. If a kid hassled one of the twins at school, he'd have me on his back as fast as my stumpy little legs could carry me. At home the four of us fended for each other and spied for each other and did whatever else we could to keep each other out of trouble.That was the unspoken law: Don't let your brothers get into trouble. We didn't verbalize it. We hardly ever talked below the surface about anything important. From Dad on down, that was the style at our house. But since each of us somehow knew the others felt the same way, discussion wasn't necessary. Besides, we were too busy struggling to keep up the rules and cover our traces when we broke them.

According to our code, the very worst thing you could do was fink on your brothers. If two of us stepped over the line and one was caught, he was expected to keep his mouth shut and absorb the full weight of the punishment. And like all good outlaws, the four of us made terrible witnesses. When Mom or Dad launched an interrogation to root out the source of a felony, we suddenly went deaf and blind. Since we almost never got away with it, I suppose it was a largely empty gesture. Still, it did allow us to salvage a bit of self-respect from the inevitable moment of retribution.

It never dawned on me that I was setting some sort of example for my brothers. Years later I realized they had watched me all through high school and college and mirrored a lot of my questionable ways: the brawling, the boozing, the messing up in school. Had I known it at the time, I don't suppose I would have changed much, but it might have made some difference. While we were still young kids living together at home, though, the only example I set for them was a strictly negative one. They saw me getting my head handed to me for being the way I was and were bright enough to conclude that wasn't the way to go. I assume that's why they went in the opposite direction. All three of them turned inward, locked away their feelings so they wouldn't show, and did whatever they had to in order to survive within the structure. They adjusted.When they were able to remember, they tried their best to steer clear of the pitfalls that landed me in the crapper. When they forgot, they remained quiet and took the punishment as it came down. We all had to take it in front of Mom and Dad, but when we got back to our rooms we could complain and bitch and moan -- and I would. They would a little, but only in a token sort of way. Then they knuckled down and did as they were told. I did, too, after blowing off a certain amount of steam, which kind of made them right and me wrong. Except that for all my fear I never gave in. I couldn't disobey the old man. I couldn't mouth off at him or be disrespectful. I had to do what he said. But I made damn sure I didn't enjoy it. I didn't do it the easy way. I stayed hot and angry and sullen. I figured that was the one right I still had coming to me.